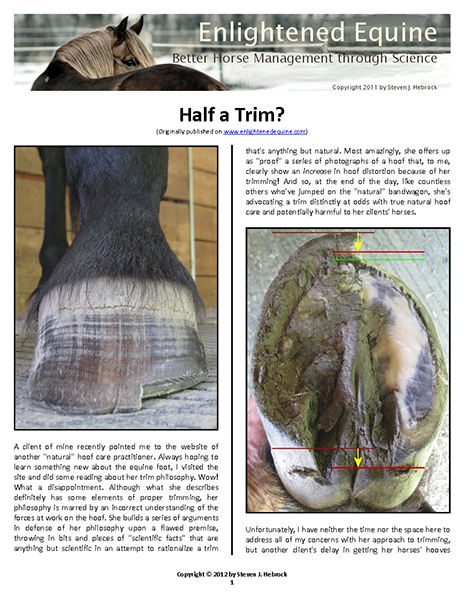

A client of mine recently pointed me to the website of another “natural” hoof care practitioner. Always hoping to learn something new about the equine foot, I visited the site and did some reading about her trim philosophy. Wow! What a disappointment. Although what she describes definitely has some elements of proper trimming, her philosophy is marred by an incorrect understanding of the forces at work on the hoof. She builds a series of arguments in defense of her philosophy upon a flawed premise, throwing in bits and pieces of “scientific facts” that are anything but scientific in an attempt to rationalize a trim that’s anything but natural. Most amazingly, she offers up as “proof” a series of photographs of a hoof that, to me, clearly show an increase in hoof distortion because of her trimming! And so, at the end of the day, like countless others who’ve jumped on the “natural” bandwagon, she’s advocating a trim distinctly at odds with true natural hoof care and potentially harmful to her clients’ horses.

Unfortunately, I have neither the time nor the space here to address all of my concerns with her approach to trimming, but another client’s delay in getting her horses’ hooves trimmed ended up giving me a convenient way to describe what I see as the major flaw in this trimmer’s philosophy. This fault, which is shared by many others, centers on the notion that “natural” hoof care involves not trimming some particular part or parts of the hoof. For some, it’s the sole; for others, the bars or frog. In this person’s case, it’s the heels. She states: “While the advice of many is to trim the heels, my advice is to leave them alone.”

The role of the natural hoof trimmer is to provide the trim nature provides; specifically, to trim the hoof as nature would trim it given the right circumstances. We have very clear examples of the end results of nature’s trimming, and can see the effects of the abrasive forces at work on a consistent, whole-hoof basis. Yet, somehow, these folks manage to separate out various parts of the hoof to trim or not trim, based on criteria that are frankly beyond me. I’ve heard some very well-known trimmers make remarks like, “If I trim a hoof and part of it grows back quickly, then I figure the horse must need that part to be long, so I don’t trim it again.” Huh?

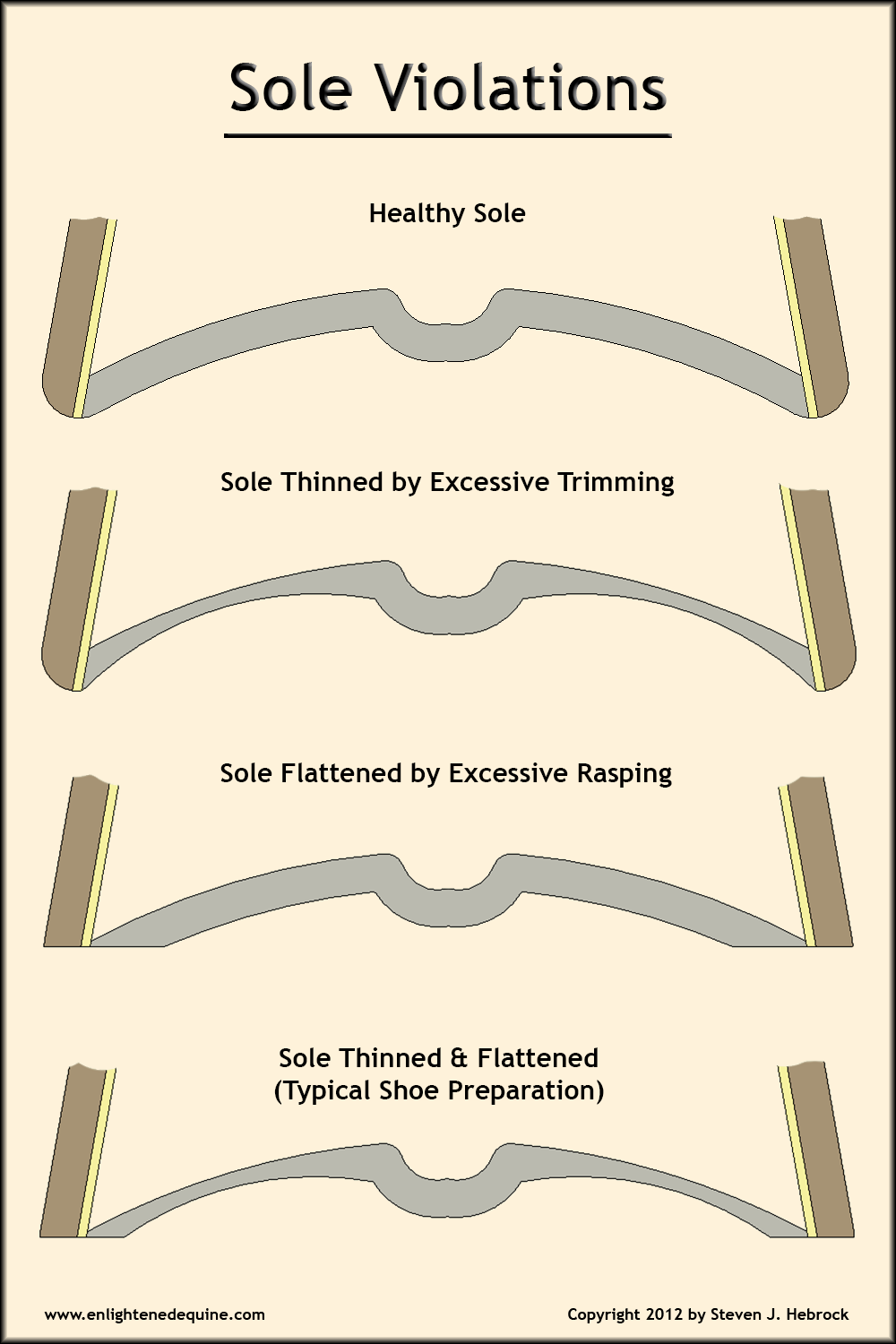

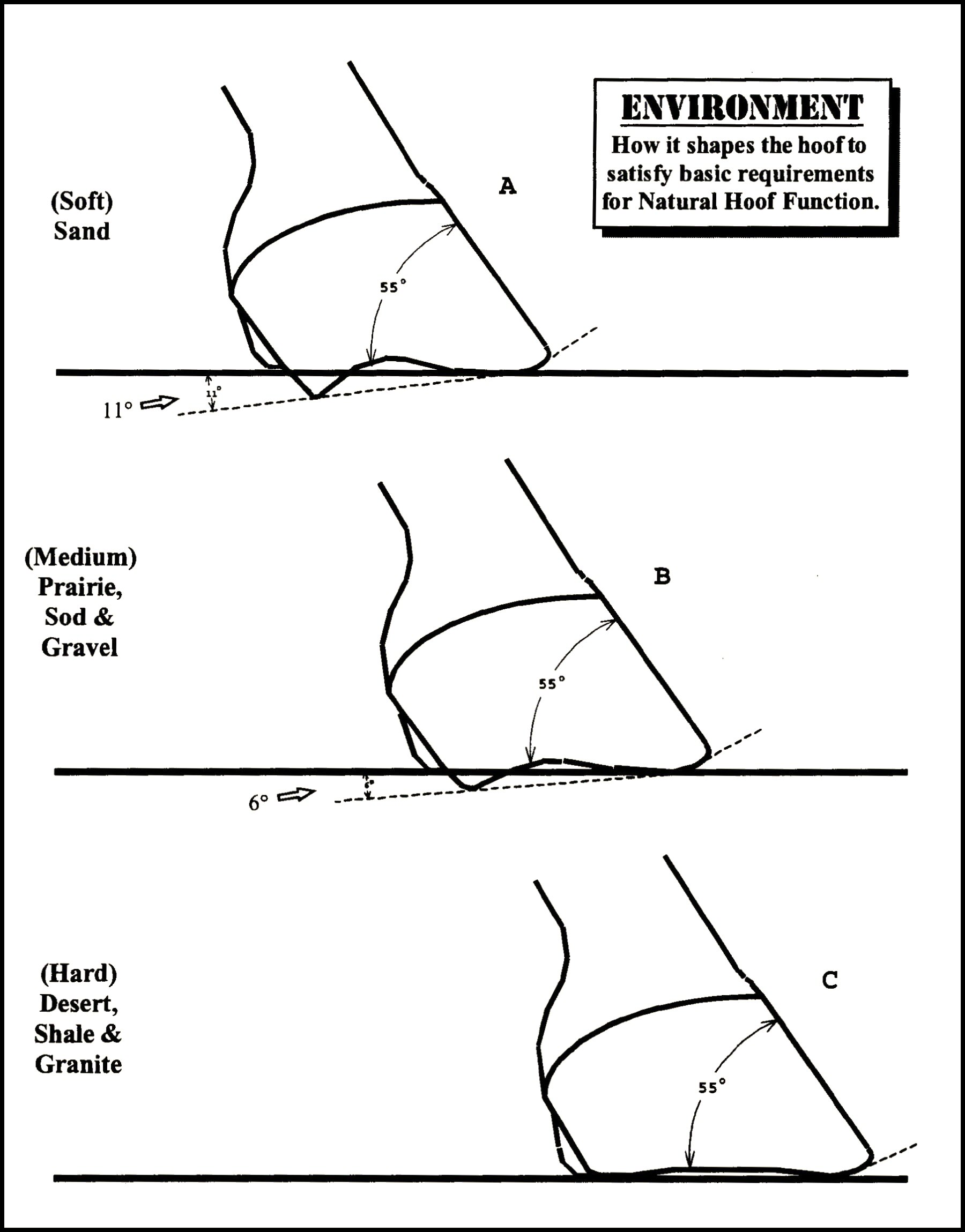

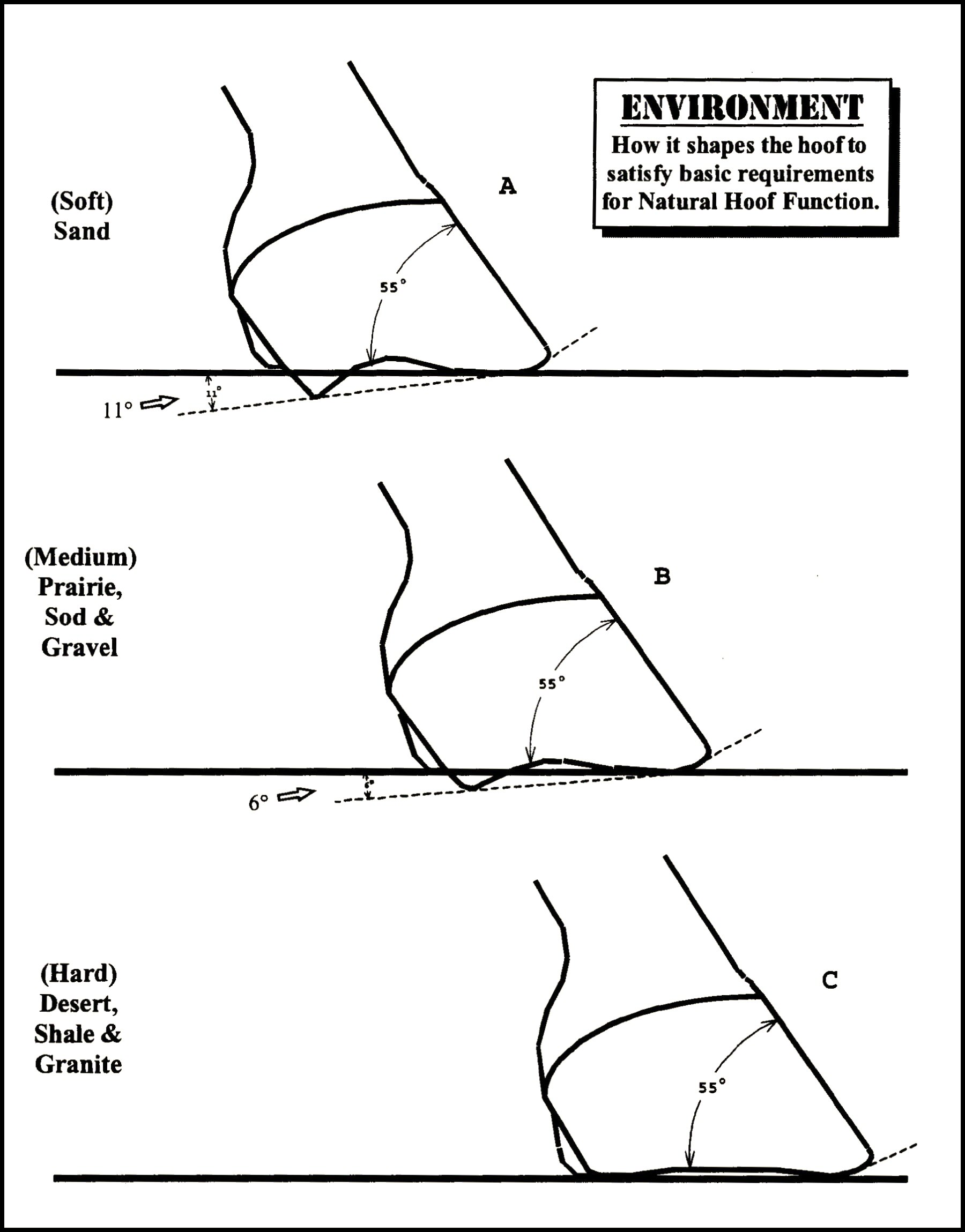

In this particular trimmer’s case, some of her comments lead me to believe her “no-heel-trim” philosophy is based on the fact that different environments produce different hoof forms. Take a look at the illustration below –

– from New Hope for Soundness, Second Edition, by Gene Ovnicek

Given sufficient movement over suitably-abrasive terrain, every horse’s hoof will look like the bottom illustration, just as documented prior to Mr. Ovnicek’s efforts by Jaime Jackson. As the terrain gets softer, less and less abrasive forces are at work on the heels, and so they grow basically unchecked. But, as noted in the illustration, the hoof maintains the same functional angle because the heels penetrate the softer terrain. So one might conclude, as I suspect this trimmer did, that since many of our horses are kept on softer terrain, the heels should be left alone.

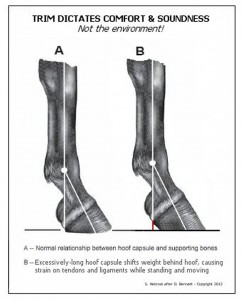

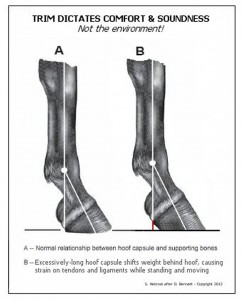

Examine the two photos at the start of this post. In the second photo, the red horizontal lines on the left half of the photo mark the ends of the toe and heel buttresses (“heels”). The red lines on the right are equidistant from the left-hand lines, and mark the trimmed position of the heels and an equivalent distance back from the untrimmed toe position. This helps illustrate the important concept that trimming isn’t just about shortening the hoof in the vertical direction; as you can see, the trimmed “footprint” of this hoof has actually moved towards the back of the  horse approximately 10% of the length of the foot, correctly placing the weight of the horse forward over his heels. So excessive length of the entire hoof, even if it’s balanced front-to-back (A-P) and left-to-right (M-L), is ultimately harmful. For a better look, check out the accompanying illustration – a revision of the one that appeared in Hoof Angles – Part 3 from Dr. Deb Bennett’s Principles of Equine Orthopedics. Incidentally, note that the contact point of the toe, indicated by the green line, has actually moved even farther back, somewhat shortening the “footprint.” Most, if not all, of that decrease is due to the “mustang roll” around the outer hoof wall. You can also, by the way, get a pretty good idea from the photo about what would happen to the “footprint” if we trimmed the toe and didn’t trim the heels!

horse approximately 10% of the length of the foot, correctly placing the weight of the horse forward over his heels. So excessive length of the entire hoof, even if it’s balanced front-to-back (A-P) and left-to-right (M-L), is ultimately harmful. For a better look, check out the accompanying illustration – a revision of the one that appeared in Hoof Angles – Part 3 from Dr. Deb Bennett’s Principles of Equine Orthopedics. Incidentally, note that the contact point of the toe, indicated by the green line, has actually moved even farther back, somewhat shortening the “footprint.” Most, if not all, of that decrease is due to the “mustang roll” around the outer hoof wall. You can also, by the way, get a pretty good idea from the photo about what would happen to the “footprint” if we trimmed the toe and didn’t trim the heels!

That’s enough about why we trim the hoof, but I need to say more about why we trim the entire hoof. There’s a reason why there aren’t, and shouldn’t be, region-specific “natural trims.” And the reason is quite simple –

Trimming the hoof as if the horse lived in the extremely abrasive environment of the U.S. Great Basin, traveling many miles per day, will always offer every horse the best chance at long-term comfort and soundness because the worst-case riding environments we subject our horses to most closely mimic those conditions.

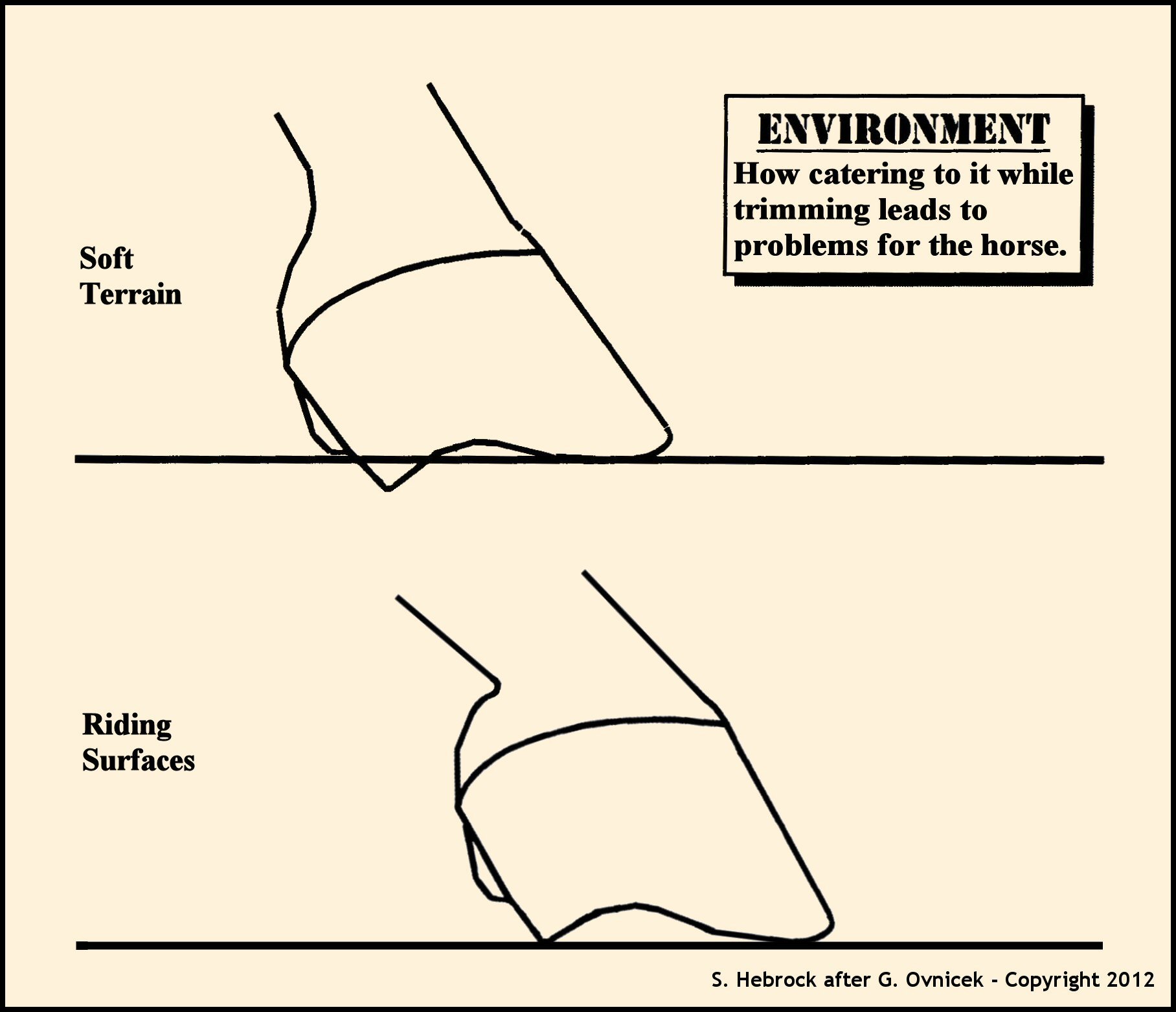

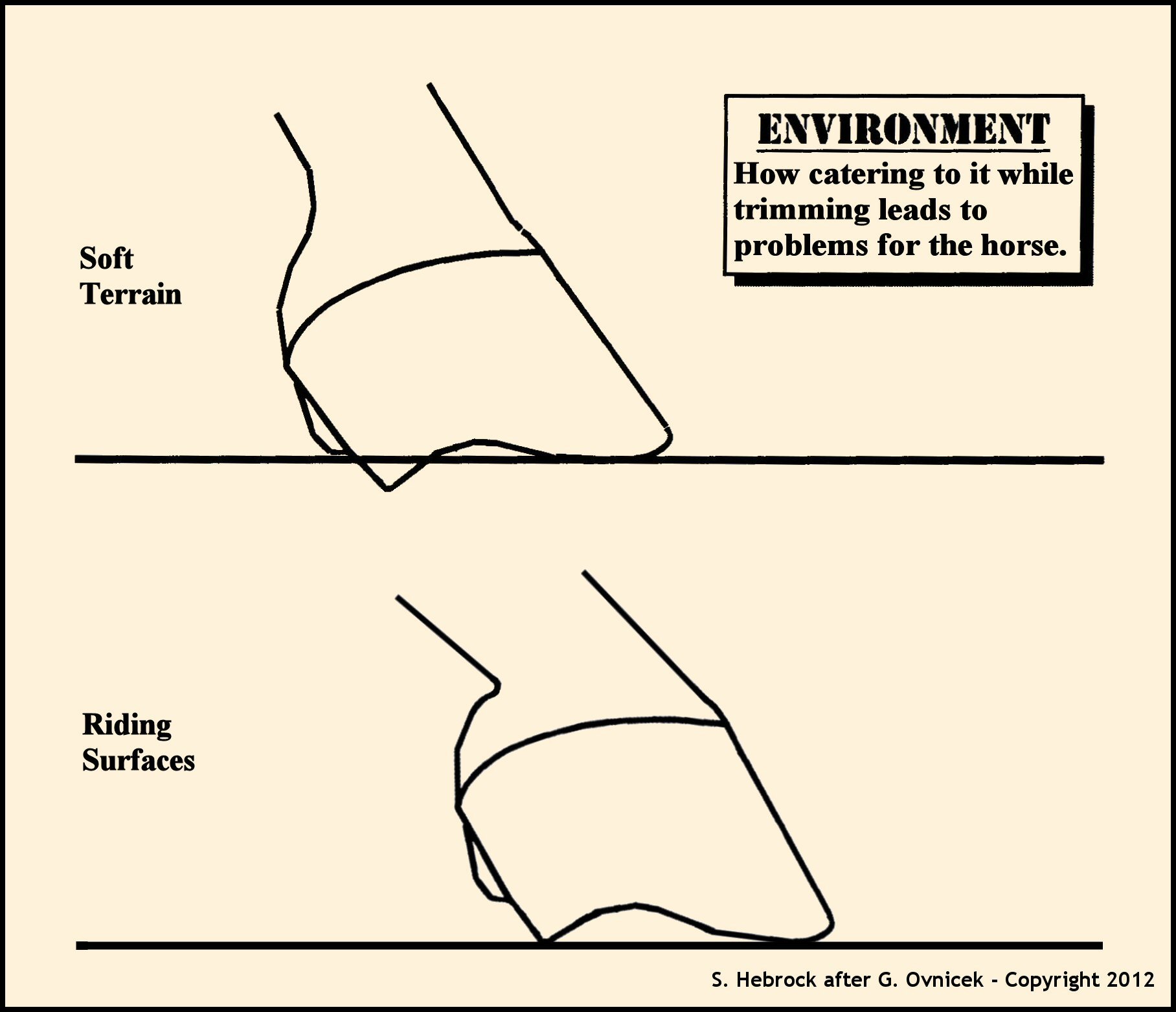

To say it another way: when we ride our horses on pavement, hard ground, or even well-packed sand, the heels cannot adequately penetrate the surface. So if the hoof isn’t properly balanced for a flat landing on an unyielding surface at the walk, the foot will be subjected to the damaging forces of jerk and concussion, as described in Hoof Angles – Part 4. So the practical form of Mr. Ovnicek’s illustration should look like this –

Hooves kept on soft terrain and ridden on medium-hard or hard terrain

We cannot – we must not – pick and choose what parts of the hoof to trim or not trim, because the U.S. Great Basin feral horse model, combined with a bit of common sense, shows that to be wholly improper. And deliberately unbalancing the hoof, as advocated by the aforementioned trimmer, can have very dire consequences for a horse unless the horse is always used in exactly the same environment the trimmer has catered to in his or her trim (highly unlikely, I might add!). The safest and healthiest trim for your horse will always entail removing all excess growth, and not a bit more, as demonstrated by the U.S. Great Basin feral horse model.

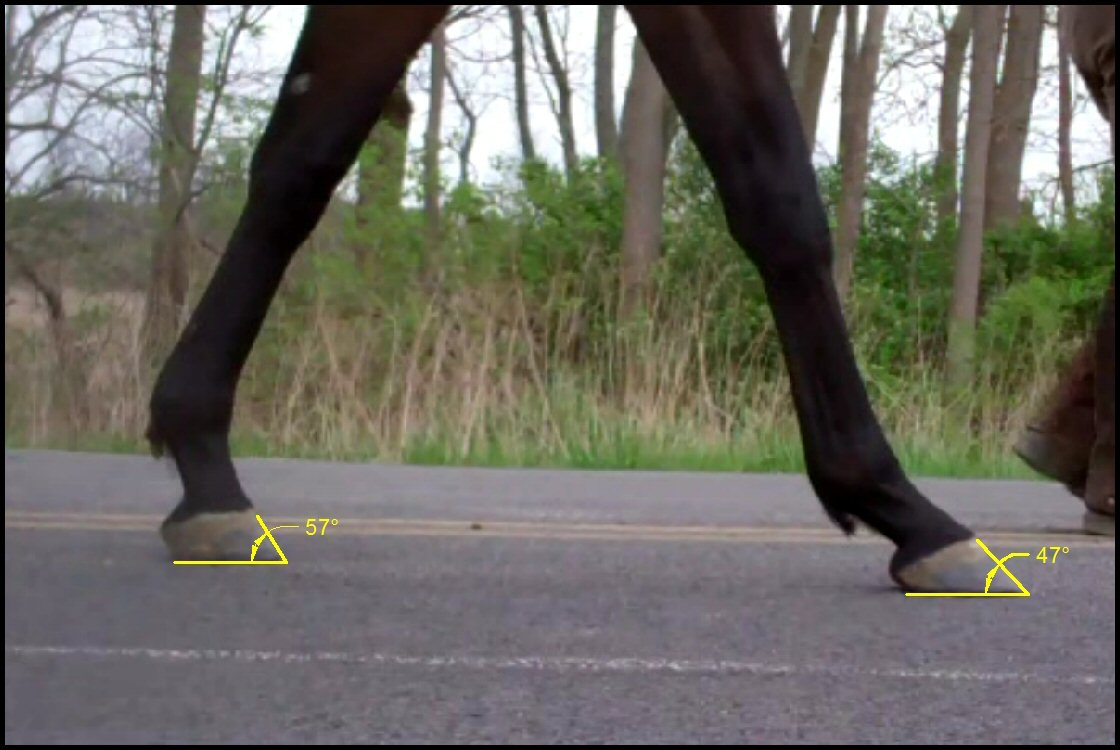

In closing, I want to share an excerpt from a video I’m working on. The first clip is of one of my clients’ horses, chosen only because of the wide concrete barn aisle. As you’ll see, the horse lands flat at the walk. The second clip, which I did not record, is of a horse whose trimmer had been mimicking the trim style he saw in a well-known book on natural hoof trimming – or so, at least, he and the owner believed. Note how the hooves, most notably the front ones, literally slam into the ground heel-first. Ouch!

– excerpt from an upcoming video about proper versus improper landings, showing the flat landing of a properly-trimmed horse followed by the heel-first landing of an improperly-trimmed horse

More soon…