Some further reflection on my last Post, coupled with conversations and comments from several readers and clients, has made me want to add a few other thoughts regarding what constitutes genuine natural hoof care.

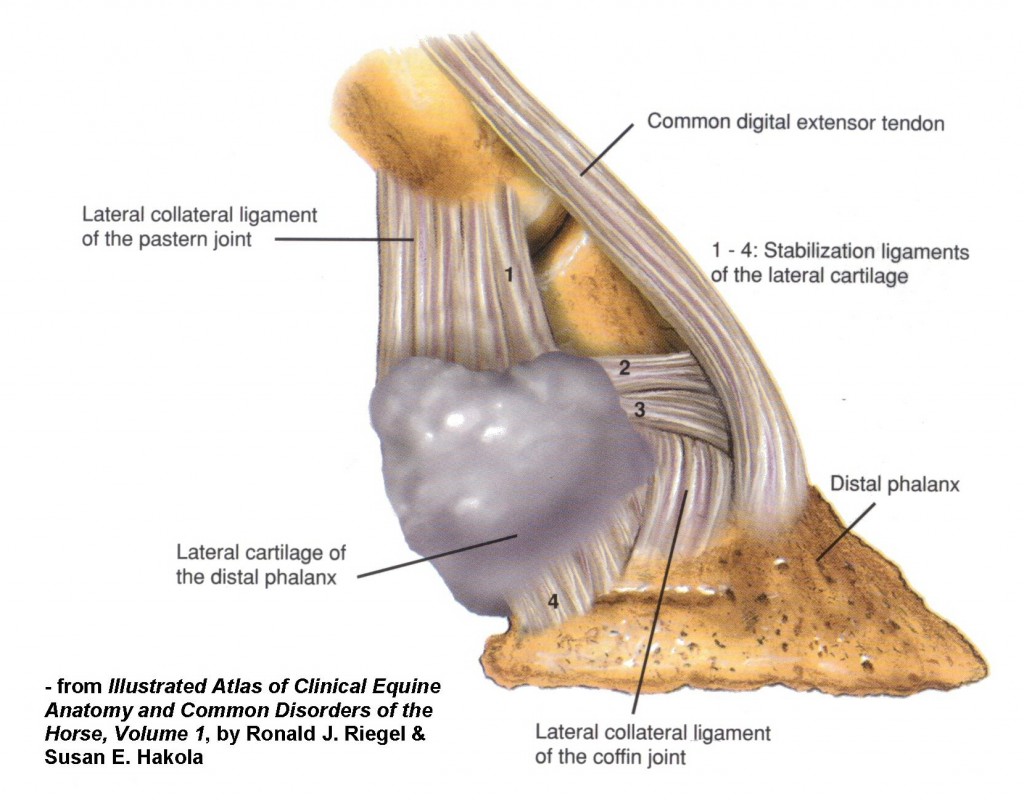

In this case, I think it’s important (and, given the plethora of folks pretending to provide natural hoof care, becoming increasingly more so) to point out that natural hoof care is absolutely not a panacea. In spite of many claims and promises to the contrary, it will not cure every possible hoof ailment. How could it? Damage is damage, and while it does offer hope for comfort and a lessening of symptoms in every circumstance (more on that in a minute), it will not fix what’s truly broken. It won’t cure ringbone or sidebone or navicular disease – assuming the diagnosis is correct (admittedly a big “if” when it comes to anything “navicular”), those are very real pathologies with permanent consequences. And anyone who suggests otherwise is doing you and your horse a disservice.

I defined natural hoof care in my last Post, but, after having just talked about what it won’t do, let me now state that what natural hoof care does have going for it is this: natural hoof care offers the best possible chance at long-term comfort and soundness for your horse, regardless of what you do with him/her and regardless of when you begin the process. Now, I realize there are people out there who don’t care about that; their entire objective is to win at whatever they’re doing with their horse. And they try to accomplish it by putting their faith in trimming and shoeing techniques that are, at best, worthless, and, more commonly, extremely destructive to their horse. And the fact that their horse is the real loser isn’t an issue for them. I’m not talking to those people here.

The people I am talking to are those who genuinely want the best for their horse. I met a rather “classic” example the other day – a woman trying to wade through the hoof care quagmire to get the best possible care for her horses. Three of them were barefoot (her preference), but the hoof care they’d been receiving was a far cry from natural hoof care. Instead, it looked like the usual prep to put on a shoe – flat bearing surface on the wall, too short in the toe, way too long in the heels, bad M/L (medial/lateral, or side-to-side) balance, and lots of bar and dead sole left on the bottom. Banging down on their heels with every step, causing not only heel pain, but upper-body pain as well. A hoof that can’t expand properly, limiting shock absorption, circulation, and sensation. And, of course, speeding up the arthritic process with the unilateral concussion. What a mess!

Her fourth horse needs (and will have) another Post devoted to fully describing his situation, but let me just say here that he’d been diagnosed with “navicular” and had been examined and “treated” by a number of vets and farriers, culminating in him being shod with things that had more in common with the Marquis de Sade than with hoof care. To make things really interesting, it was undoubtedly one of the worst trimming/shoeing jobs I’ve ever seen. This horse was sore!

These are the situations that make me angry. This is when I imagine seeing that vet and farrier subjected to the same torture they’ve put the horse through. Is ignorance a crime? No – of course not. But bad work, and, worse, recommending things that a 10-year-old with even a modicum of common sense could see are illogical, should be. Pretending to know things when you don’t should be as well. And the whole topic of knowing what you don’t know reminds me of an experience I had some years back…

When, after several years of contact with Jaime Jackson via email and telephone, I finally went to study with him in person, I’d asked him to bring along “challenging” cadaver hooves to trim since I was pretty confident about trimming “normal” feet. So after trimming a couple of pretty typical hooves, he pulled out the sorriest-looking mess of a hoof I’d ever seen – including in photos – and handed it to me. I studied it for a minute or two, and Jaime asked me how I was going to proceed. I started off my plan by saying, “I think,” only to have him interrupt me. “You think?” he said. “You THINK??? Listen, if you don’t know exactly how to proceed, you have no business touching this hoof!” After another minute of studying the awful thing, I simply handed it back to him. A big smile appeared on his face, along with the words, “That’s exactly what I wanted you to do!” I knew what I didn’t know, and he knew it, too! We then trimmed that hoof together – still the worst one I’ve ever seen – and dissected it when we finished. It didn’t even have a coffin bone left; it had been completely reabsorbed!

That was a very valuable lesson for me. No horse should ever pay the price for a care provider’s ignorance. The good news for these four is that it’s now over, and what a joy it was to see all of them walk off more comfortably after being properly balanced. Does the one horse truly have navicular disease? I don’t know yet – I’ve not seen any imaging, and it’s too soon to tell clinically. But he’s very obviously more comfortable, so, regardless of the ultimate diagnosis, he’s on the path to being as sound as he can be.

So, just a few more points about natural hoof care before I end this Post. The list, by the way, isn’t in any particular order and isn’t intended to be comprehensive. Also note that I’m still not describing the physical characteristics of a properly-trimmed hoof. That’ll have to wait for yet another Post.

- Natural hoof care is right for every horse, but not for every owner. If your expectations are unreasonable, you’re not going to be happy even though your horse will be happier. The worst kinds of situations are those where the horse has been shod his entire life, stands 24/7 in a urine-laden stall eating the horsey equivalent of ice cream and bonbons (lots of processed feed and treats), and the owner wants you to “do that barefoot trim thing” so he/she can ride him 20 miles over rocks tomorrow. Not happening.

- Natural hoof care makes sense, both viscerally and intellectually. If it didn’t, I wouldn’t be doing it. If it doesn’t to you, you shouldn’t be doing it either. Period.

- Natural hoof care takes time. The hoof grows fairly slowly, and achieving proper hoof form and function is very likely to be measured in months, not days or even weeks. The entire body often has to re-balance itself after years of uncomfortable and/or abnormal movement. Don’t expect to have a new horse tomorrow when you’ve both been living with the old one for years.

- Natural hoof care is still atypical. Your horse’s hooves are likely to look very different from every other horse in the barn, so be prepared to hear about it from your friends, your trainer, the barn manager, and every other person anywhere nearby. Know that you’re absolutely doing the best for your horse, and remind yourself there’s plenty of data to support your position. Stand up for your horse’s right to be sound!

- Natural hoof care is a commitment. You can’t “sort of” do it – you’re either in or out. That means it matters whether or not you’re consistent in using the same (qualified) person, even if you have to wait a week or two longer than you might like. While it’s easy to tell yourself, “Oh my gosh, it’s been ___ weeks, and she’s got a couple of chips. I’ve got to get her trimmed today, so I’ll just get ol’ Charlie to give her a quick trim,” resist the urge. Your horse will be fine. Don’t risk undoing all the progress that’s been made by panic over what, to the horse, amounts to nothing.

- Natural hoof care is a whole-body process. There are other factors besides trimming that contribute to hoof form, function, and quality, including what a horse eats, how much he/she moves, the type of terrain over which he/she moves, and (to a much lesser extent) genetics. Don’t imagine merely getting a proper trim is the end of it any more than buying a guitar makes me Jimi Hendrix.

- Natural hoof care is about the balanced hoof, which leads to healthy hooves and balanced movement. Short and well-rounded for efficiency. All the dead sole material exfoliated for proper expansion and shock absorption. Absolutely minimal concussion at impact to stave off osteoarthritis and other joint and bone degradation. And no “corrective” anything – ever. The trim allows the horse to move properly; it does not make the horse move in a particular way. And it’s not about angles, lengths, or any other numbers, just so you know.

‘Til next time…