– advertisement from Central Semiconductor

Yes, I know it’s been far too long since I’ve posted an article, but life seems to have a way of interfering with my writing! The good news is that I now have several articles well under way, and so will try hard to keep the gaps shorter.

I had to laugh when I saw the above image as part of an advertisement in one of my technical magazines a couple of months ago, because it seemed as if they knew I was going to be writing this article on heel-first landings and wanted to help illustrate the problem with an easily-understood picture! But that statement will probably make more sense later on…

I want to be absolutely clear right from the start: this notion that horses are “supposed” to land heel-first is, without a doubt, one of the most widely-propagated and dangerous misunderstandings currently in vogue in the horse world. I had intended to start posting my series of articles on navicular disease, but since navicular disease and landings are so closely connected, and because I decided I simply couldn’t bear to listen to one more horse owner or hoof care provider tell me that horses should land heel-first, I decided my priority had to be to weigh in on this very important subject now. In fact, this article could just as correctly be called “Navicular Disease – Part 0.” So although I’ve briefly mentioned in the past that a properly-trimmed horse will land flat at the walk (see, for example, Hoof Angles – Part 4), I haven’t yet discussed the logic behind that assertion at length. By doing so here, I hope to save a lot of horses from a lot of problems on down the road.

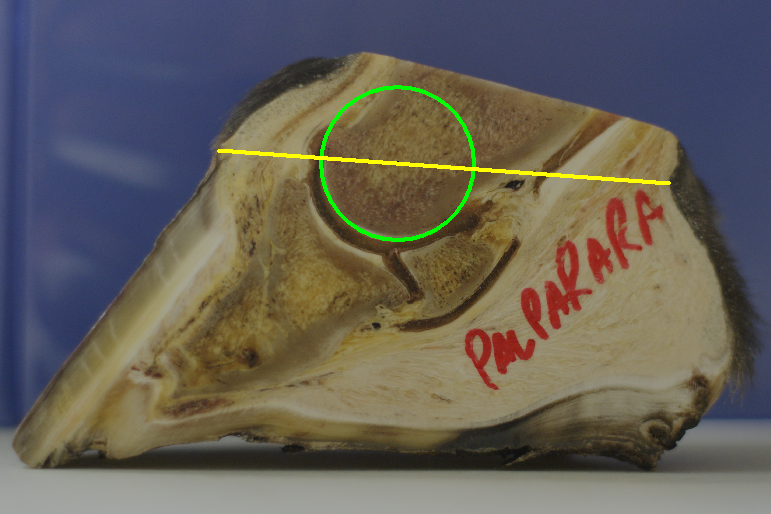

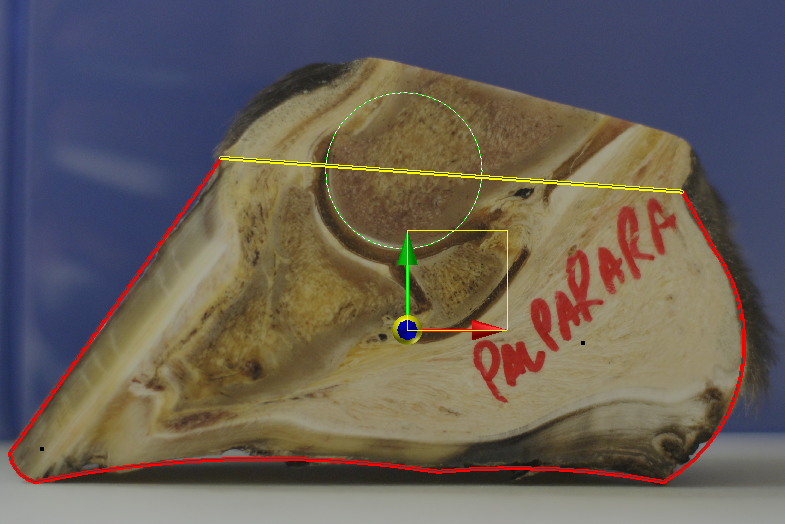

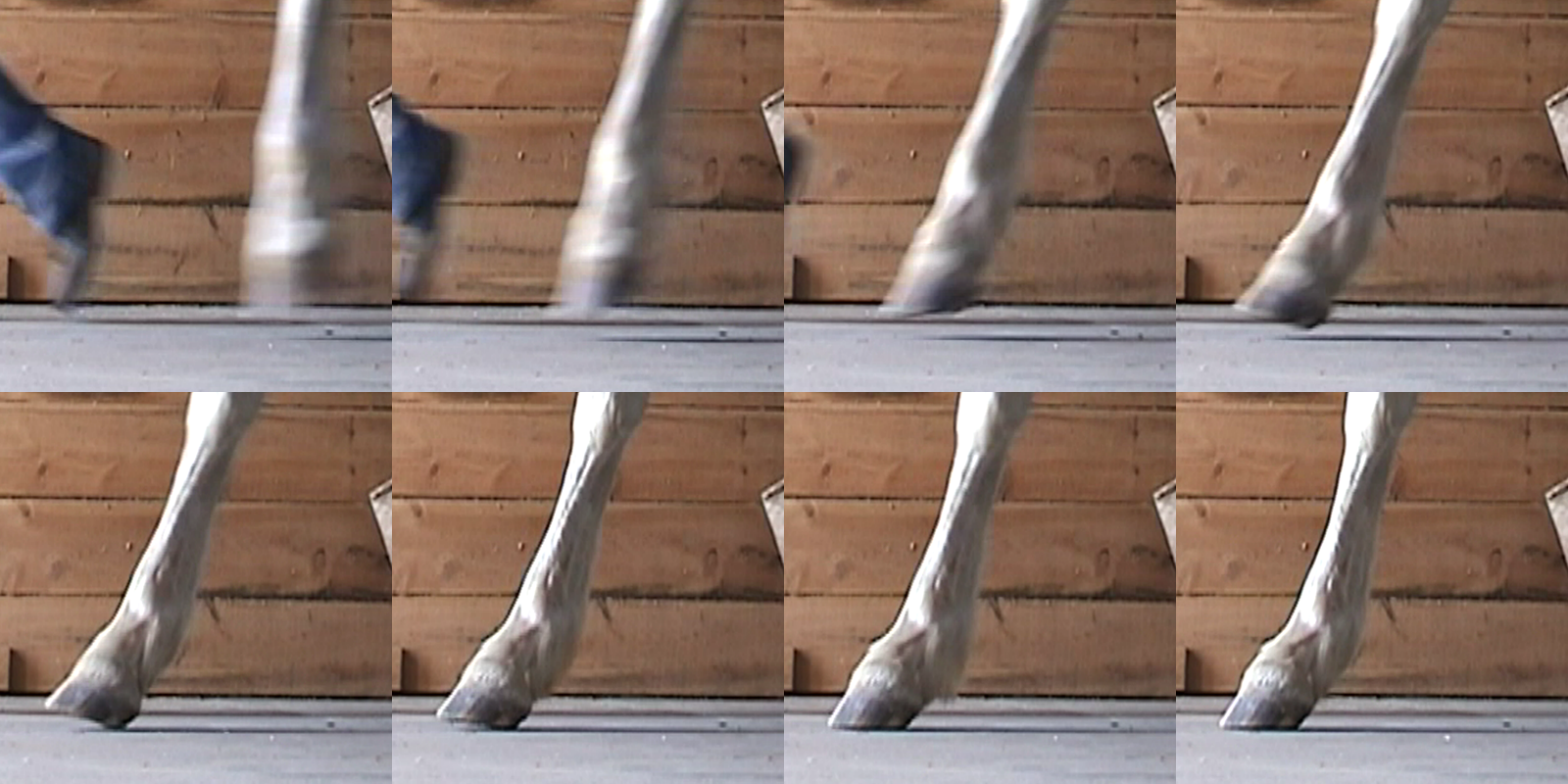

A heel-first landing on an improperly-trimmed bare hoof

To be fair, I also need to tell you that I, too, used to believe horses should land heel-first because years earlier I’d read a passing statement in renowned equine pathologist Dr. James Rooney’s book Biomechanics of Lameness in Horses in which he said that horses land flat to slightly heel-first (emphasis added). He did not, however, mention the conditions, such as gait or speed, under which he believed this to be the case, nor did he state whether or not this was a theory based on physiology, or merely an observation of horses he’d encountered. Interestingly, later parts of the same book strongly contradict the heel-first part of his statement, which he then supports with both theory and observation, and his most recent writings on the subject clearly state that the horse should land flat at the walk. In his webpage discussion of feral hoof form entitled “The Shape of the Equine Hoof,” for example, he says:

At the slow walk, the hoof usually contacts the surface over the whole bearing edge of the hoof wall; that is, the foot impacts flat-footed.

Unfortunately, this fallacy about heel-first landings still persists, largely (I believe) because one particular barefoot clinician has stated it many times in his clinics, and because humans tend to land heel-first. But long before I’d read Dr. Rooney’s most recent work, or even his earlier work more carefully, I’d already come to the conclusion that common sense tells us a properly-trimmed horse – whether by nature or by human – must land flat at the walk. In talking to many people over a number of years about this subject, I’ve found that non-horse people, especially technical types, tend to immediately understand why, while many horse people seem to struggle with it. But I’ll do my best to make it clear!

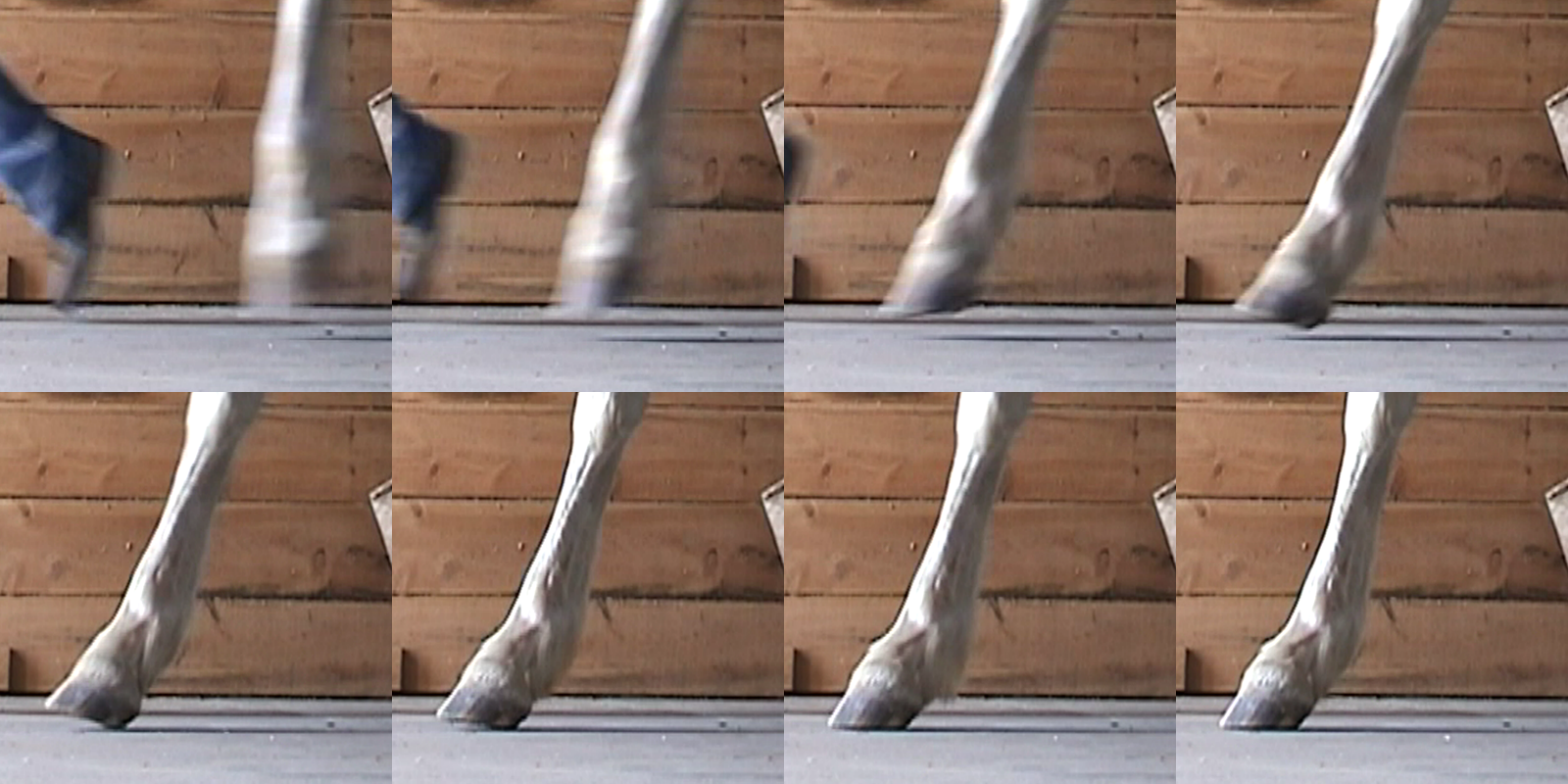

A proper landing on a properly-trimmed bare hoof

In this installment, we’ll take a look at two things we need to understand before really discussing the landing problem at length: first, the differences between biped and quadruped limb construction and movement, and second, the issues surrounding how humans perceive landings.

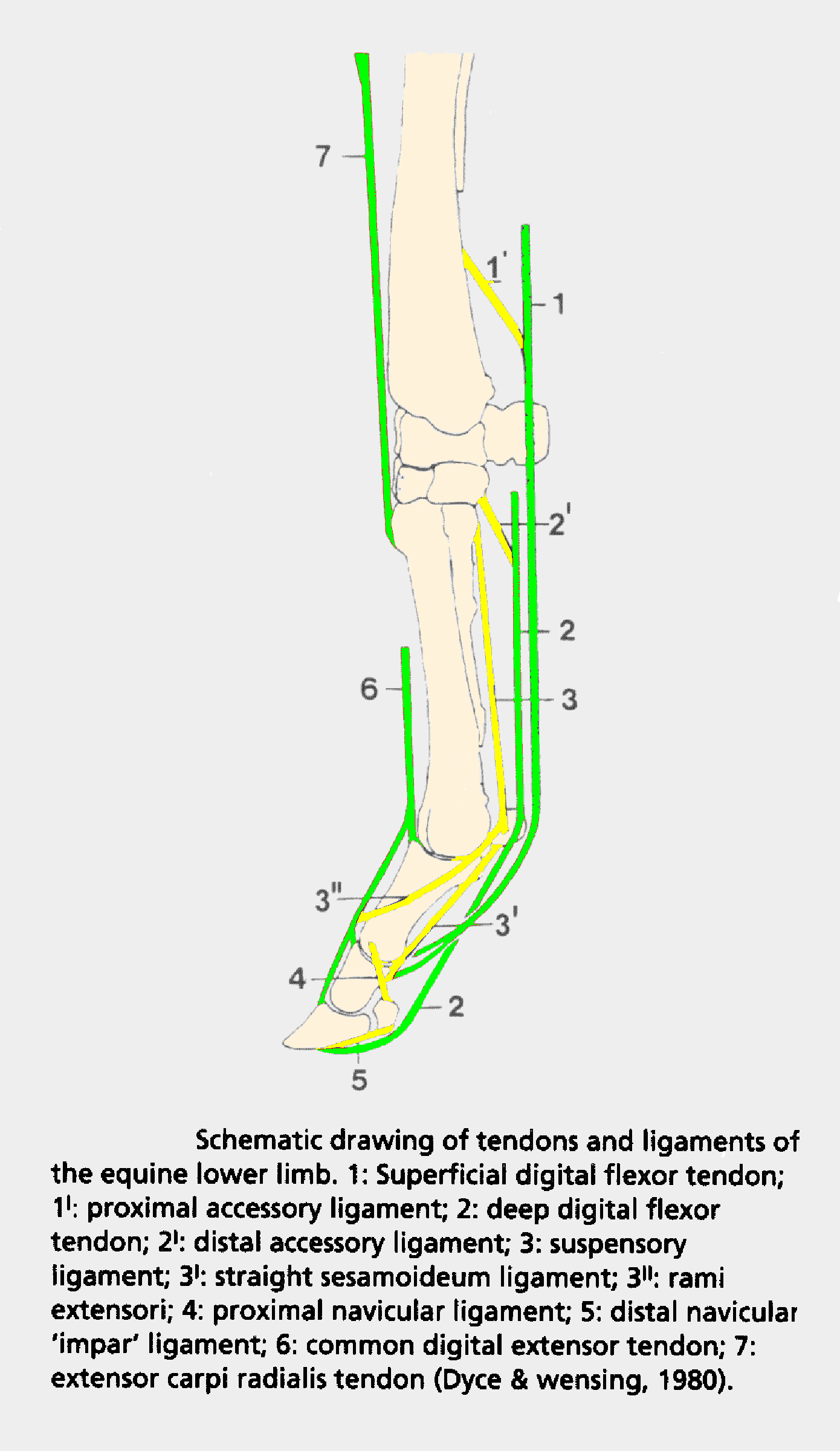

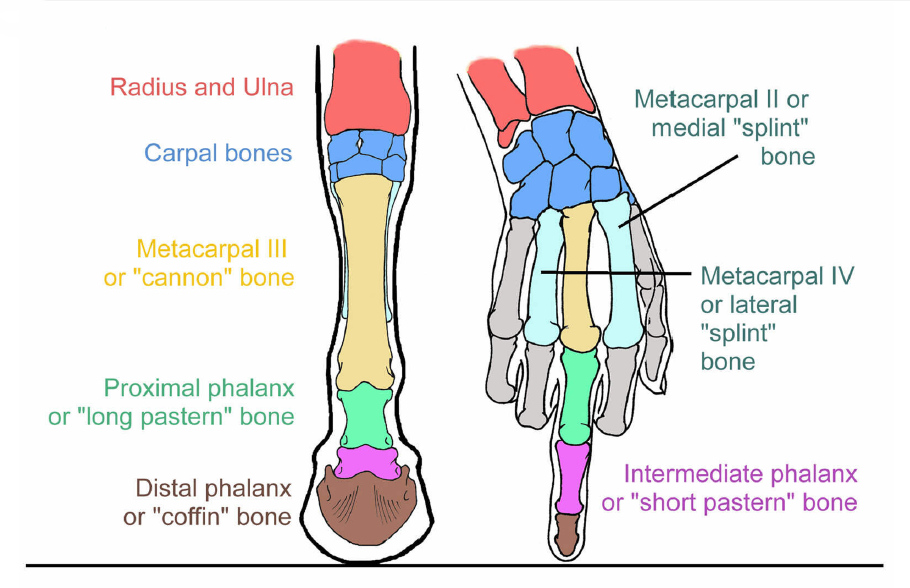

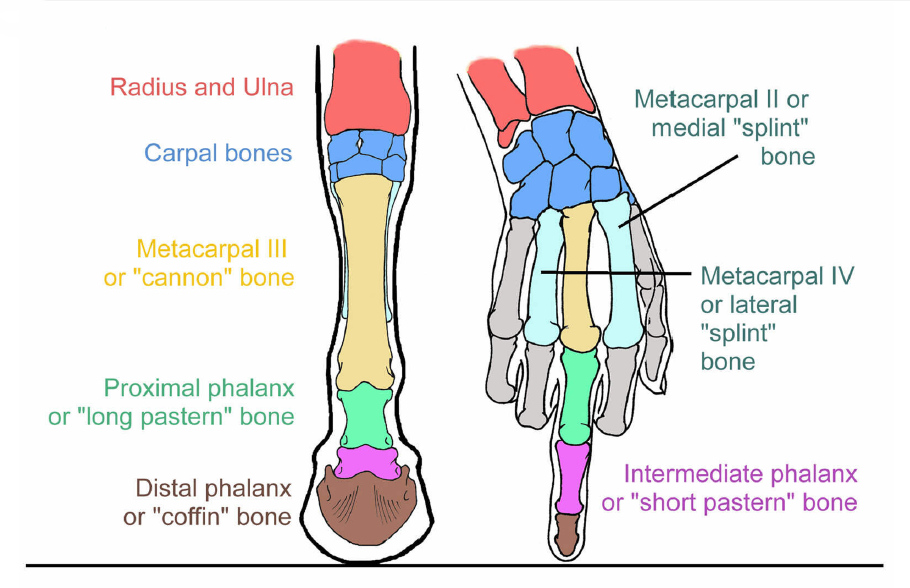

As you’ll see in this image from Dr. Deb Bennett’s Principles of Equine Orthopedics Part 1 comparing the equine and human forelimb, they’re very different in both structure and function –

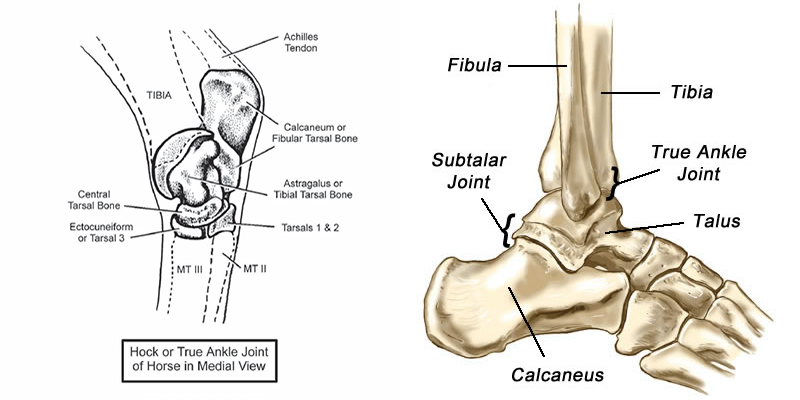

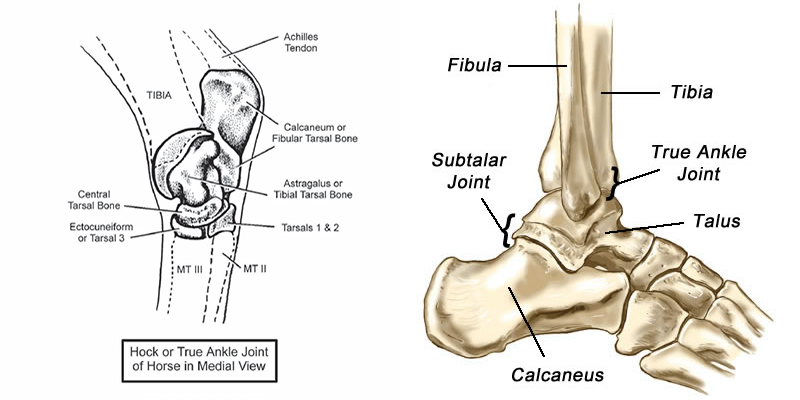

So in the forelimb, what we generally refer to as the horse’s “knee” is in fact his wrist, or carpus. The horse actually walks on a hoof attached to what would be the last joint of our middle finger. In the rear limb, the horse’s ankle is the hock joint, and not the fetlock as may seem intuitive. The image below shows their comparative anatomy; the hock image is from Principles of Equine Orthopedics Part 1, and the ankle image is from www.kidport.com –

As we consider differences in the way we move, it’s important to note the consequences of these anatomical distinctions. The human ankle consists of an inverted cup of bone perched on top of a ball, stabilized by ligaments. It’s quite compliant by design, and although it flexes fairly readily in both the front-to-back (A-P) and side-to-side (M-L) directions, it’s less stiff and has a far greater range of motion in the A-P direction. In contrast, the forelimb diagram above shows the lowest joint in the equine limb to consist of much broader surfaces designed to articulate only in the A-P direction. With good reason, I might add; if you’ve ever rolled your foot to the inside in a misstep, you can imagine the “train wreck” that would occur if a horse were able to do that at 40 MPH! That complete lack of lateral flexibility, incidentally, is also the reason so-called “corrective” trimming & shoeing is such a long-term disaster, as I pointed out in What Makes it “Natural Hoof Care?”.

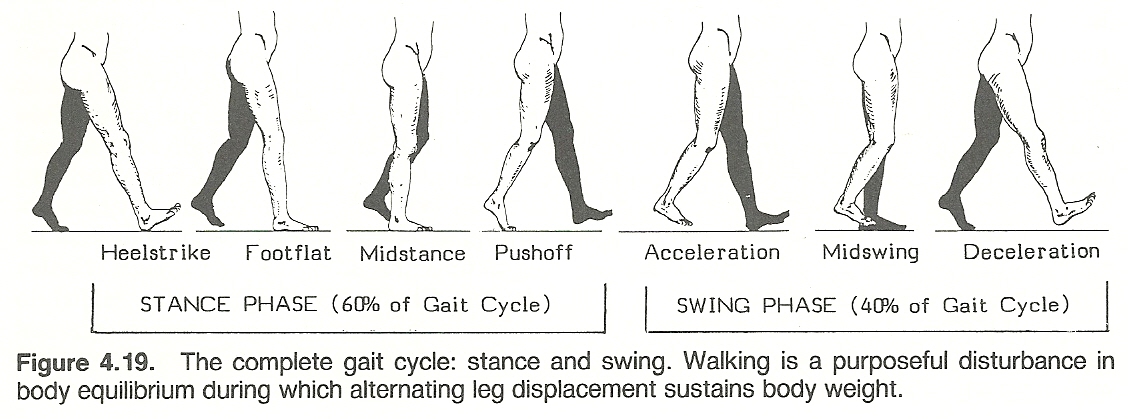

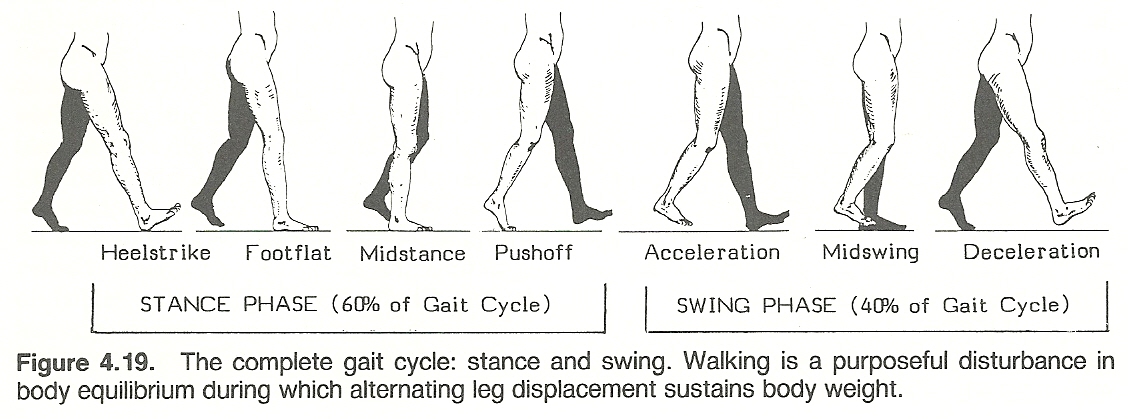

The following image from R. C. Schafer’s book entitled Clinical Biomechanics: Musculoskeletal Actions and Reactions (2nd ed.) is very helpful in understanding biped locomotion. Pay particular attention to where the torso is with respect to the leading and supporting limbs –

And here’s what the author has to say about the mechanics of walking:

Biomechanically, walking can be considered as a series of continuous losses and recoveries of balance in which the rhythmic play of muscles narrowly averts toppling. Steindler refers to the basic sequence of movements in walking as a “series of catastrophes narrowly averted.”

In other words, walking in a particular direction involves shifting your center of mass in the direction you wish to go, and then “catching yourself” with the leading leg as your mass comes over that leg. In essence, you fall forward to move forward. And if your foot is in a neutral position – basically perpendicular to the axis of your leg – it strikes the ground more and more heel-first as your stride length increases.

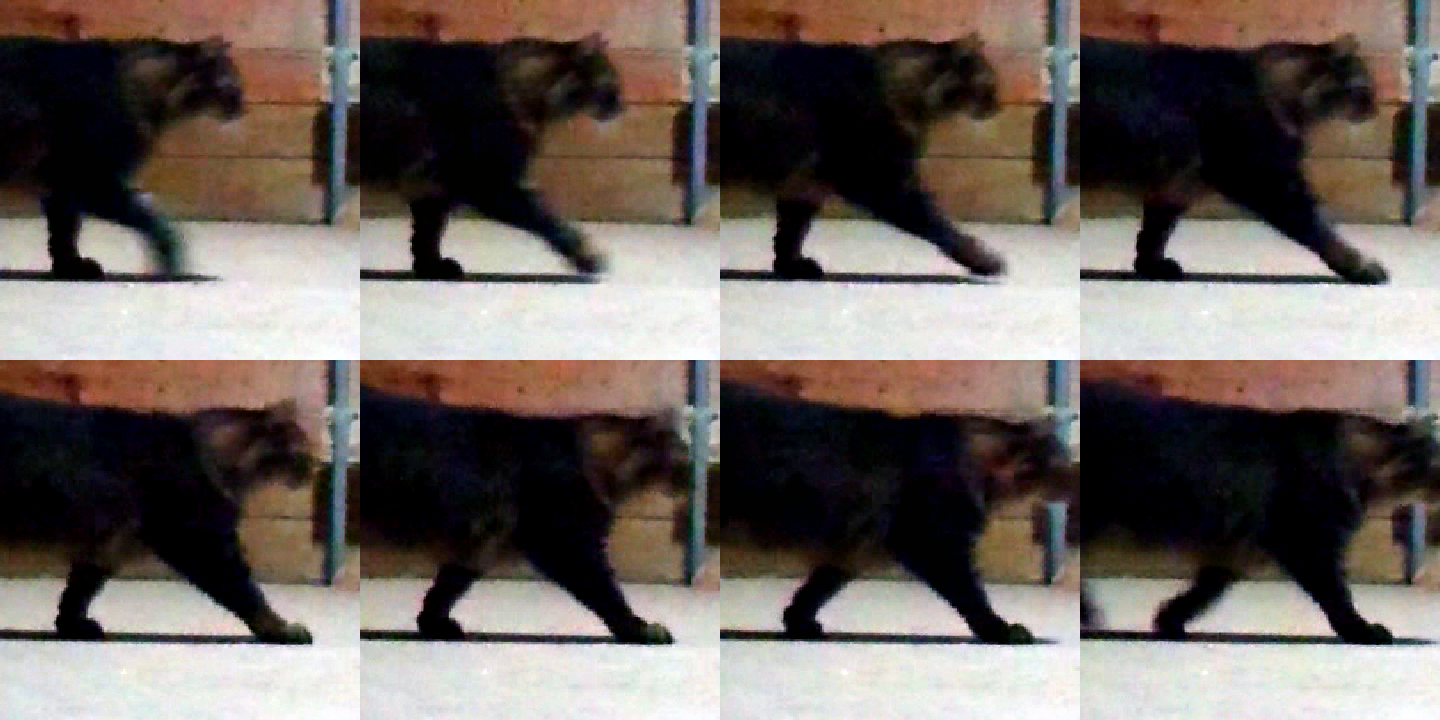

The quadruped, on the other hand, doesn’t walk like that because their center of mass is never ahead of the leading limb while it’s loaded. The cat in the following (bad!) photos walked through my video setup while I was recording a horse. As you can clearly see, he’s stable on 3 legs and his center of mass is behind the leading leg. Like your horse, he doesn’t have to “fall” onto the leading leg like you and I must do to move forward. You’ll also note he’s definitely not landing heel-first, and I didn’t even have to trim him! –

Someone forgot to tell this cat he’s supposed to be landing heel-first…

The other part of this background information has to do with how humans perceive things. Back in 2008 when I began to seriously question this notion of a heel-first landing being “correct,” I became convinced that humans probably aren’t able to see differences in timing between heel contact and toe contact. So I wrote to a number of researchers in the field of visual perception, and posed the following question (since I couldn’t assume they knew anything about horses!):

An observer watches (but does not hear) someone slap both hands down on a tabletop in a brightly-lit kitchen. At what interval between slaps will the hands striking the tabletop appear to be a simultaneity?

The responses I received were all nearly identical, but Dr. Ken Norwich, Professor Emeritus at the University of Toronto’s Institute of Biomedical Engineering provided the following answer with some qualifiers:

How bright is the light used to make the observation? The interval you seek will depend on the illumination. What is the background to the images of the hands? Let us assume that it is a black background, but contrast will also affect the measured interval. Probably the interval is very close to the reciprocal of the flicker fusion frequency i.e. the frequency of flicker where an observer sees a steady image rather than a flickering light. This frequency is about 55 seconds (-1), so the interval you are looking for is at least as great as 0.02 seconds, or 1/50th of a second, and that is for a very bright image.

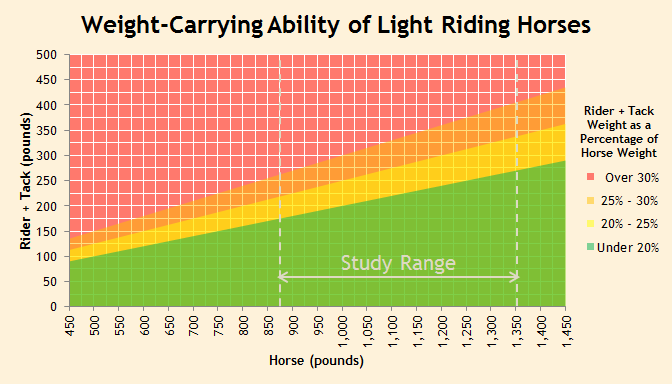

So in brightly-lit conditions against a high-contrast background, the limit of a human’s perception is in the neighborhood of 20 milliseconds. Any timing difference between heel and toe contact shorter than that will be seen as a flat landing. And just how many barns have you been in where you find “brightly-lit conditions against a high-contrast background?” Darned few, if any, in my experience!

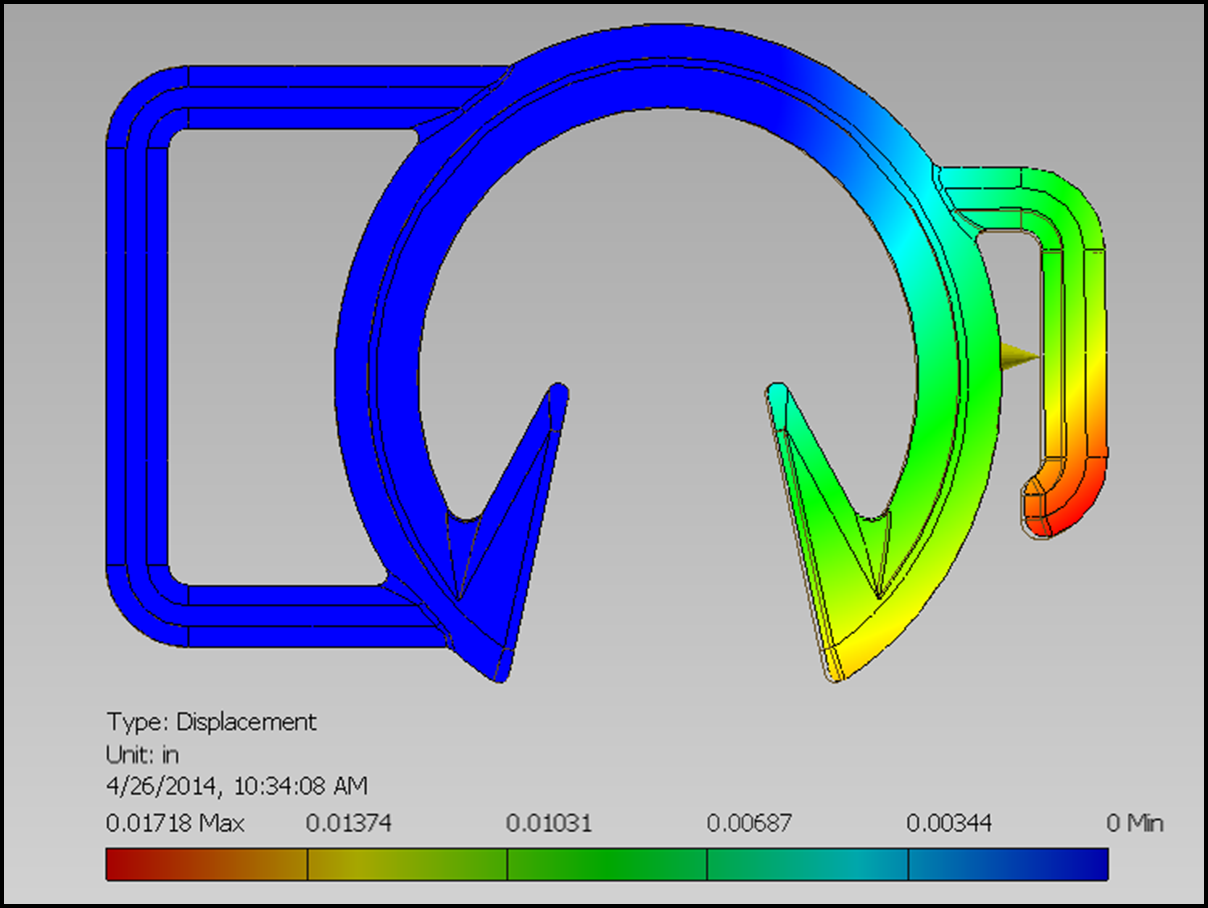

To help put things into more meaningful terms, observe the first set of hoof images in this post. This heel-first landing, from heel contact to toe contact, was quite obvious to me at normal speed, and measures approximately 80 milliseconds.

And now take a look at the following two landings –

In both of these cases, the heel-first landing wasn’t particularly apparent at normal speed, and only became obvious when I slowed down the video. Although the background isn’t very high-contrast, the lighting was reasonably bright. They both also measure approximately 20 milliseconds from heel down to toe down. In fact, of the 6 heel-first landings I happen to have slow-motion video of as I write this, the average heel-to-toe contact time was only 32 milliseconds – alarmingly close to the limits of human perception under ideal laboratory conditions.

Therein lies the rub: if you can see an obvious heel-first landing, the landing must be very heel-first in order for you to perceive it as such! And soon I’ll explain why that’s a serious problem for your horse.

So those are the first two hurdles to overcome in this discussion of landings in horses: regardless of what you may observe about human movement, you cannot apply it to equine movement because horses and humans are fundamentally different; and, the timing of a heel-first landing strains the limits of human perception, so you can’t be absolutely certain of anything without using additional tools such as slow-motion video.

More soon…