One of the constant frustrations I encounter is nicely illustrated by the preceding clip from the 2004 – 2008 television show Wildfire. No, I’m not talking about chipped hooves and the common perception that they’re a problem; I hope I’ve adequately addressed that issue in earlier posts. What I’m talking about instead could perhaps be called the “expert syndrome,” which is when someone with a small amount of knowledge in a particular subject area feels qualified (and compelled) to offer his or her opinion on the subject to an extent that’s far in excess of what he or she actually knows.

I want to be absolutely clear here that I am not saying these people are stupid or incapable of learning. I’m talking about the gaps every person alive has in his or her knowledge. For example, I’m probably the most ignorant person on the planet when it comes to sports. I have no interest in the subject, and I know nothing about it. But most importantly, I know I know nothing about it and therefore refrain from commenting on it. That distinction is the subject of this article.

The “expert syndrome” is extremely common and certainly not confined to the horse world. For example, when I worked full-time designing professional audio products, a colleague once complained that a reviewer for the leading industry publication had written a rather bad review of one of her company’s new products, describing in technical detail a very specific problem with its performance. So she had the engineering department measure and re-measure samples of the product in an attempt to identify and fix the problem. Trouble was, they couldn’t find the problem; in spite of their $100,000-plus testing facilities, they simply couldn’t get the problem to show up. After about a week of this, she called the reviewer to ask him about the test conditions he’d used to test the product for the review. His answer? “I didn’t actually measure anything, but I heard the problem while listening in my living room.”

I won’t even bother describing the differences between objective measurements done under very controlled laboratory conditions and one person’s subjective opinion in his living room, but I’m sure you get the idea. The more amazing part of this situation is not that he gave very specific numbers in his review as if he’d measured the product, but that he apparently thought nothing of writing a bad review of the product (which could’ve had dire consequences for the company) based on absolutely no objective information!

In the equine world, this often translates to some trainer or owner freely offering advice or making some proclamation as if it were based on actual data rather than anecdotes or speculation. Yes, I know it’s just a television show, but how many Wildfire fans nevertheless ended up believing that horses must be shod to avoid “risking a chip”? Even within the story line of the show, there’s nothing about this young woman’s history that would put her in a position to make such an authoritative comment on hoof care.

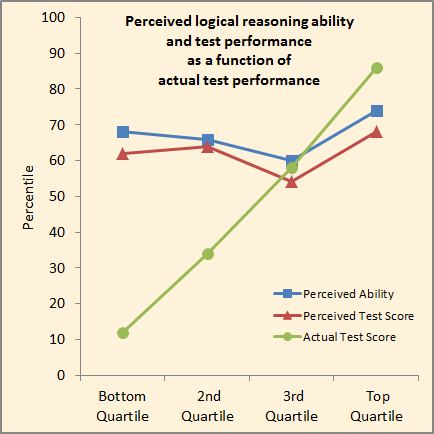

Some folks at Cornell University have actually measured this misperception of self- knowledge, and reported their findings in a paper authored by Justin Kruger and David Dunning and published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology entitled “Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments“. In this study, the authors asked people to assess their knowledge of a particular subject area, and then tested them on that subject. Following the test, they also asked each participant to assess how they thought they’d performed on the exam. The results for logical reasoning ability are reproduced below –

As is obvious, the people with the least amount of subject knowledge grossly overestimated both their knowledge and their test performance. And not just by a small amount; their actual knowledge ranged from approximately one-half to only one-sixth of what they thought they knew! That truly frightens me, because the data suggests that half of the population overestimates its knowledge of a particular subject to a very significant degree.

The big problem, as the title of the paper points out, is that people don’t know what they don’t know. Based on their study, the authors make four “predictions” about the connections between competence, metacognitive ability (the ability to “know what one knows”), and inflated self-assessment, which I’ve summarized below –

- Incompetent individuals will dramatically overestimate their ability and performance relative to objective criteria when compared to their more competent peers

- Incompetent individuals will be less able than their more competent peers to recognize competence when they see it, whether their own or someone else’s

- Incompetent individuals will be less able than their more competent peers to use information about the choices and performances of others to form more accurate impressions of their own ability

- Incompetent individuals can gain insight about their shortcomings, but this comes by making them more competent, thus providing them the metacognitive skills necessary to be able to realize they have performed poorly

So the bad news is really the inability of these “experts” to know they’re not experts, which means it falls to the rest of us to try to sort things out. And that’s not always easy to do, because if we were experts in the subject area in question, we wouldn’t be seeking the advice of others! So it’s almost the classic “Catch-22.”

What can the horse owner do? Well, the study shows us that as a person’s actual subject knowledge decreases, his or her perception of their knowledge increases. So the most questionable sources would seem to be the individuals who freely offer advice about aspects of equine management that, logically, one wouldn’t expect them to have knowledge of, have nothing in their backgrounds that suggests knowledge of the subject area in question, and/or otherwise offer vague credentials such as “because I love horses” or “because I’ve been around horses my entire life.”

Unfortunately, and contrary to popular opinion, this also includes many veterinarians when it comes to hoof care. Logically, a veterinary student cannot spend much time on any particular aspect of the horse, since, in four years’ time, they have so much to learn – mostly about small companion animals. It’s not possible for them to spend more than a very small fraction of their time (maybe a class or two) on the equine digit. Yes, we horse owners tend to expect them to have the knowledge, but it’s simply not logical to assume they have it. After I posted Toy Story, I received a number of comments from horse owners and other hoof care professionals lamenting about similar experiences. Here’s one comment from a very well-trained and highly-experienced trimmer –

When I began to trim I asked my farrier, who had moved away, about barefoot trimming. He told me to keep records of at least the first year of my trimming and figure out what the success rate was for lame horses that I trimmed. He had spent years as the orthopedic shoer for the Florida vet school. He told me that the vet/farrier combination had less than a 30% success rate for bringing lame horses back to soundness; that most of what they did was simply extending the horses’ usability for a couple more years. My first year of trimming had an 85% rate in returning horses to work under saddle, many of those with a veterinary recommendation for euthanasia, After that, I was off and running with barefoot trimming.

Board-certified veterinary surgeon Neal Valk, who teaches in our training program, has told me similar things; that, even as a “super vet” from an education perspective, he was taught very little about hoof care, and what he was taught was aimed at getting a bit more use out of a horse, with the full knowledge that once the owner went down the “corrective shoeing” route, it was only a matter of time before it no longer “worked.” But this post has gotten much longer than intended, and I’ve got to wrap it up!

I see this lack of actual knowledge and the subsequent propagation of misinformation as a very real problem in the horse world, and I like to discuss this topic in my workshops because I want horse owners to not only be able to recognize suspect information when they encounter it, but also to halt its spread when possible. So question everyone and everything, and do your level best to share only well-researched sources of information supported by objectively-credible credentials. We all have an obligation to our horses to stop inaccurate information.

Please do your part.