There doesn’t seem to be an end to what I can find to say about hoof angles! Several of my previous posts have mentioned the consequences of hoof imbalance, and it’s now time to start being more specific about the problems that can, and do, arise from an improper landing due to an out-of-balance hoof. This installment will touch on consequences involving bones and soft tissues.

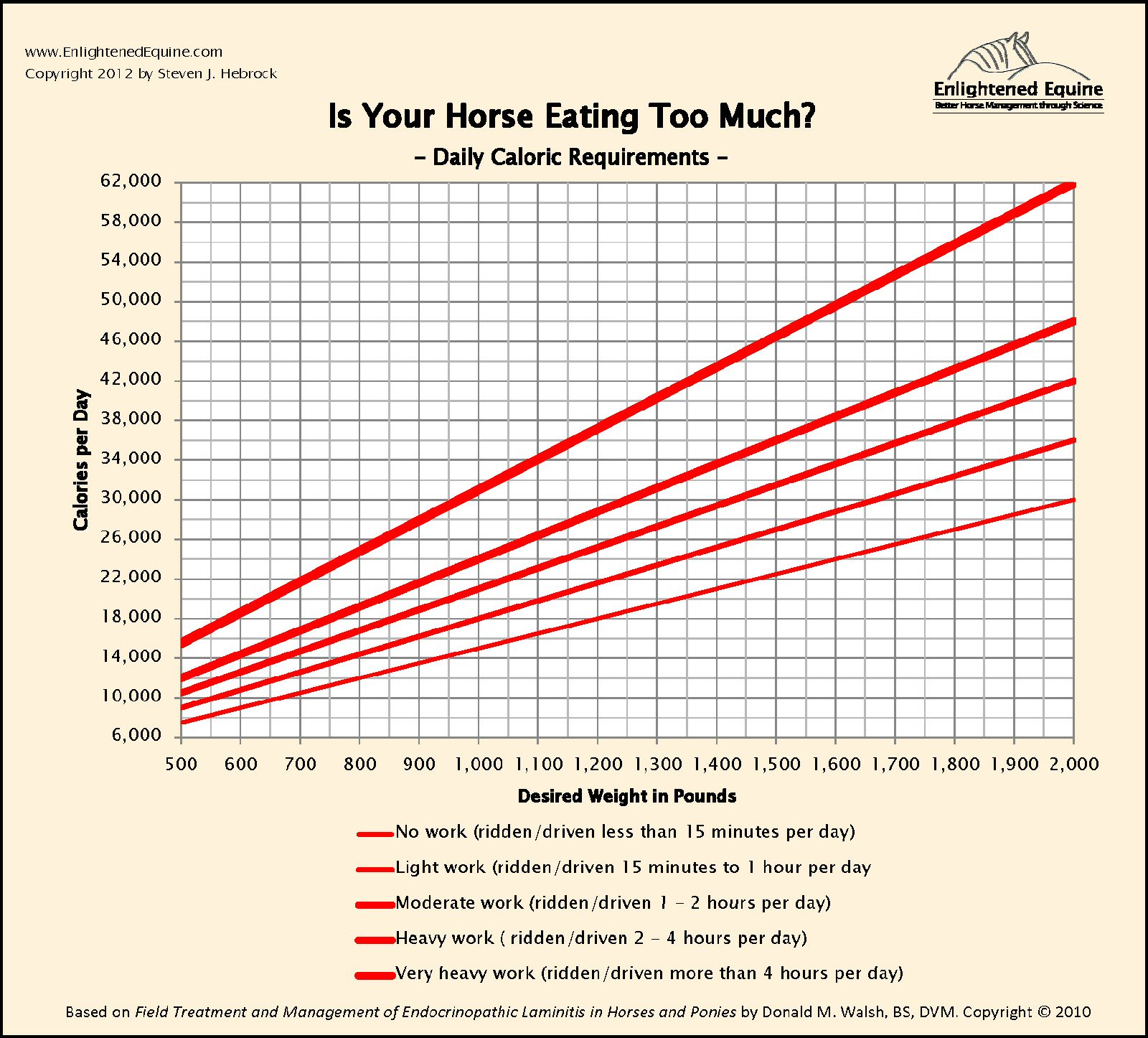

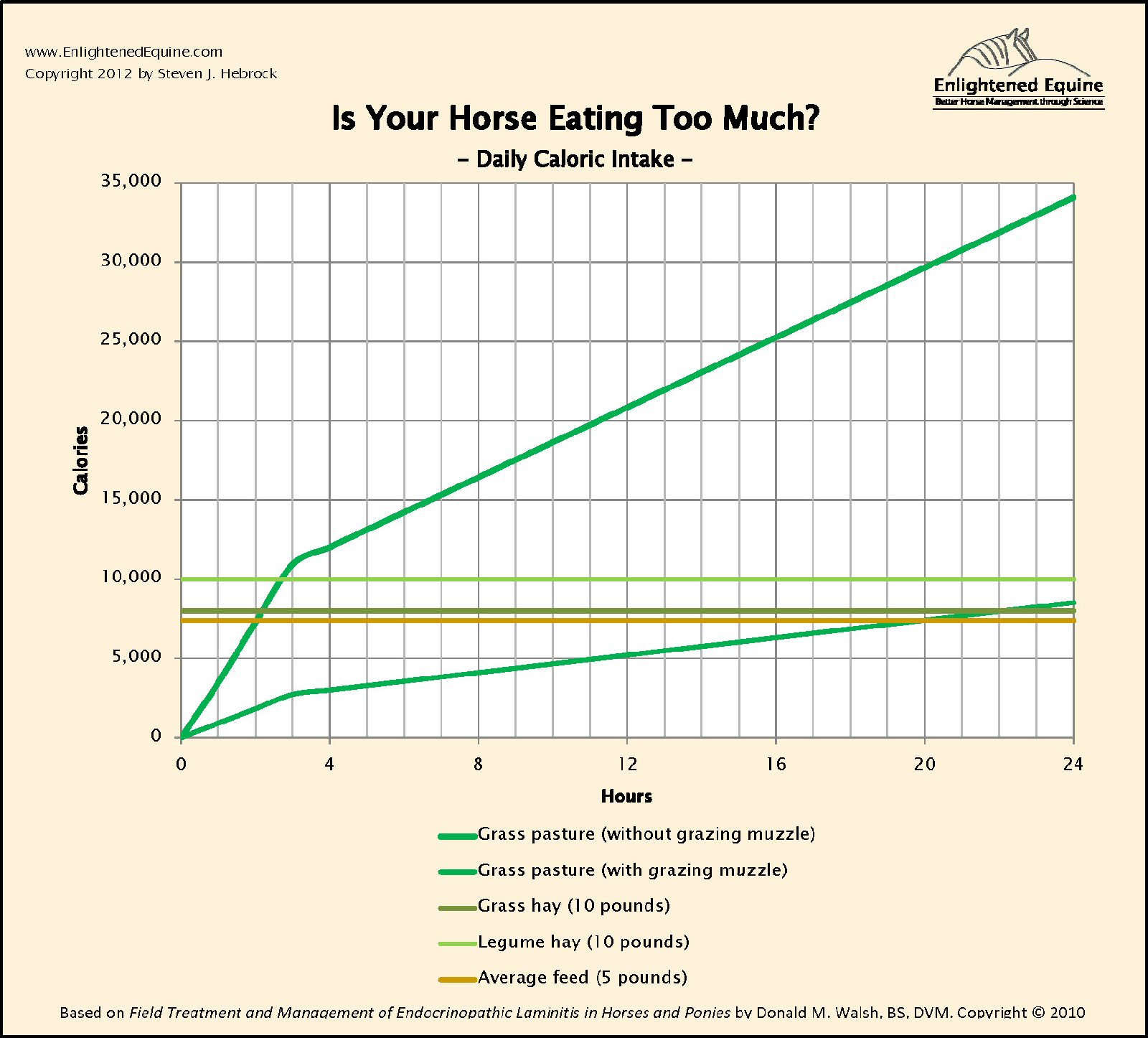

The severity of any particular problem is directly related to a number of factors, including: the horse’s conformation, the type and degree of hoof imbalance, the length of time the hoof remains out of balance, the work the horse does while unbalanced, and the type of terrain the horse moves over while unbalanced.

First of all, most horses do not suffer immediate and catastrophic ill effects from hoof imbalance. If that were the case, there would be far more lame horses than sound ones, since, in my experience, more than 9 out of 10 horses have some degree of imbalance. Instead, the effects of imbalance are often not seen until later in life, similar to human health problems associated with things like smoking, poor diet, and exposure to loud sounds. But since my objective in hoof care is the long-term comfort and soundness of your horse, I believe it’s important to understand and address these issues before they become problems at the clinical level.

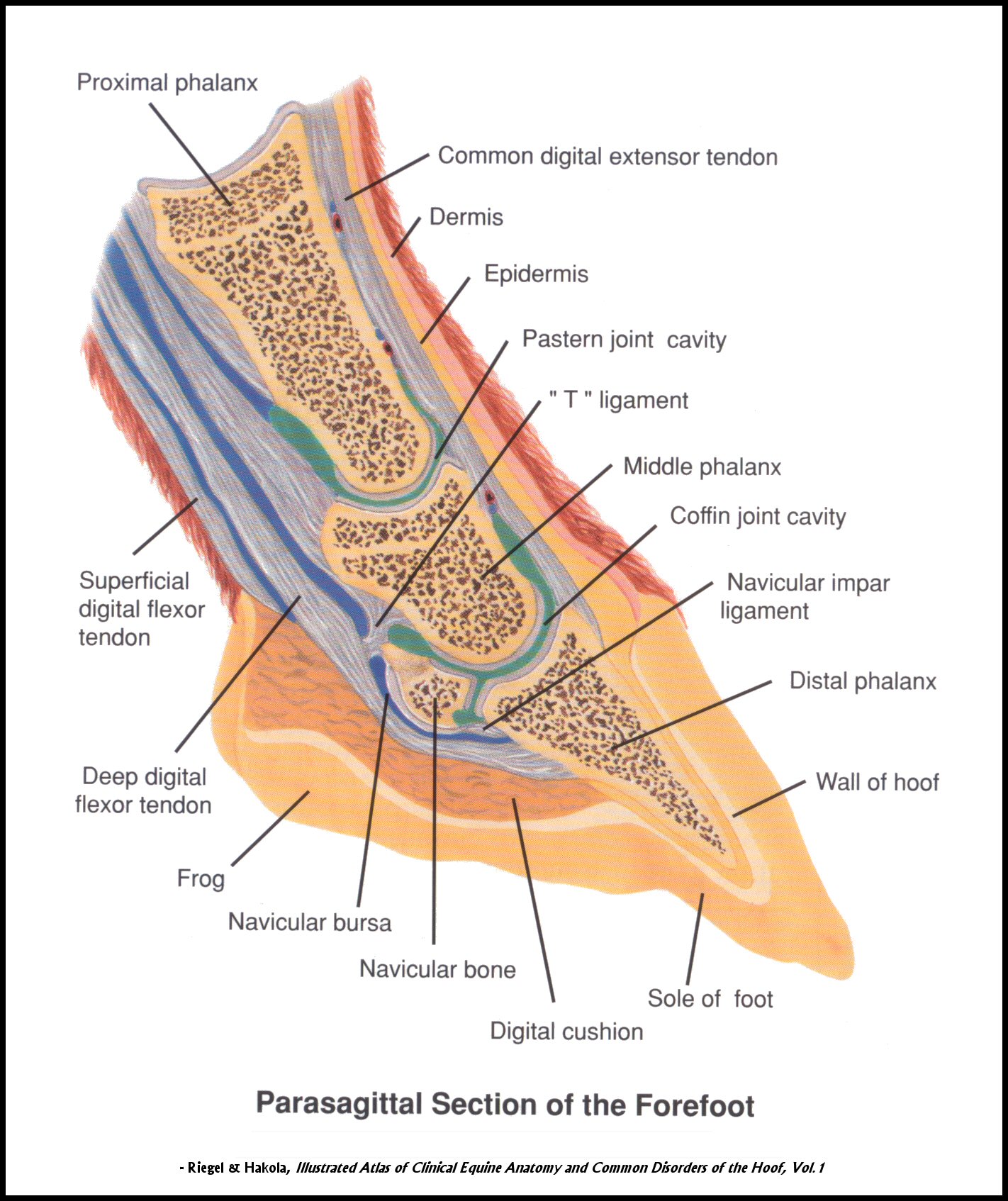

The immediate problems that do occur from extreme hoof imbalances are lamenesses due to strain on tendons and ligaments. These sorts of issues more often appear to be connected to large and sudden changes in hoof length and/or angle that can occur when the horse is trimmed, rather than to absolute balance. When a large amount of hoof wall is removed, the abrupt change in tendon and ligament tensions can leave a horse uncomfortable for a few days following trimming.

The more serious problems stemming from long-term imbalance are those related to jerk and concussion. Once again, Dr. Deb Bennett in Principles of Equine Orthopedics –

The dirty little secret of all connective-tissue cells is that they really “want” to become bony. This is because, like bone, their ultimate structure is strands of the protein collagen, which has a great affinity for calci-apatite, the mineral substance which makes bones hard. When they detect strain, connective-tissue cells respond by coating collagen strands with calci-apatite….To “talk” connective-tissue cells into depositing calci-apatite requires only a little stimulation. This normally comes from gene signals, but stimulation by electric impulses, chemical irritants, or allergens can also start it. More importantly for real horseshoeing situations, so can vibration. Vibration comes to horses in two forms: as jerk, which occurs when ligaments or tendons are sharply pulled on; and as concussion, which occurs when something pounds on them (or when they pound on something).

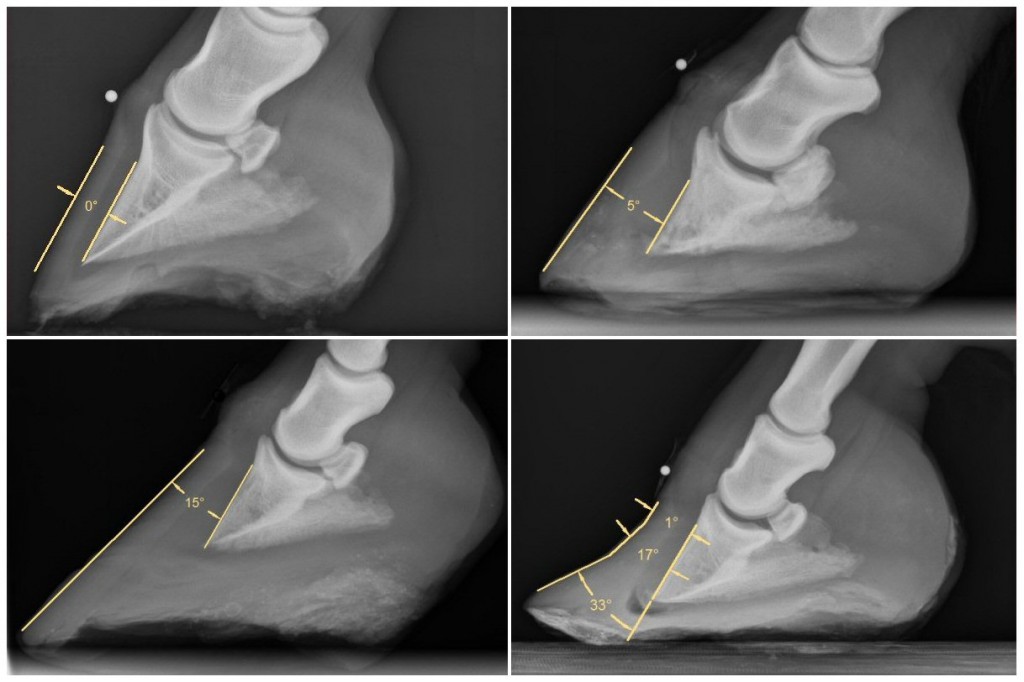

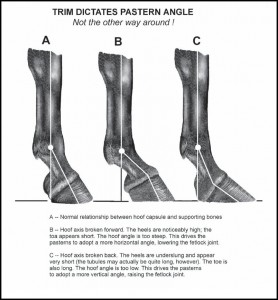

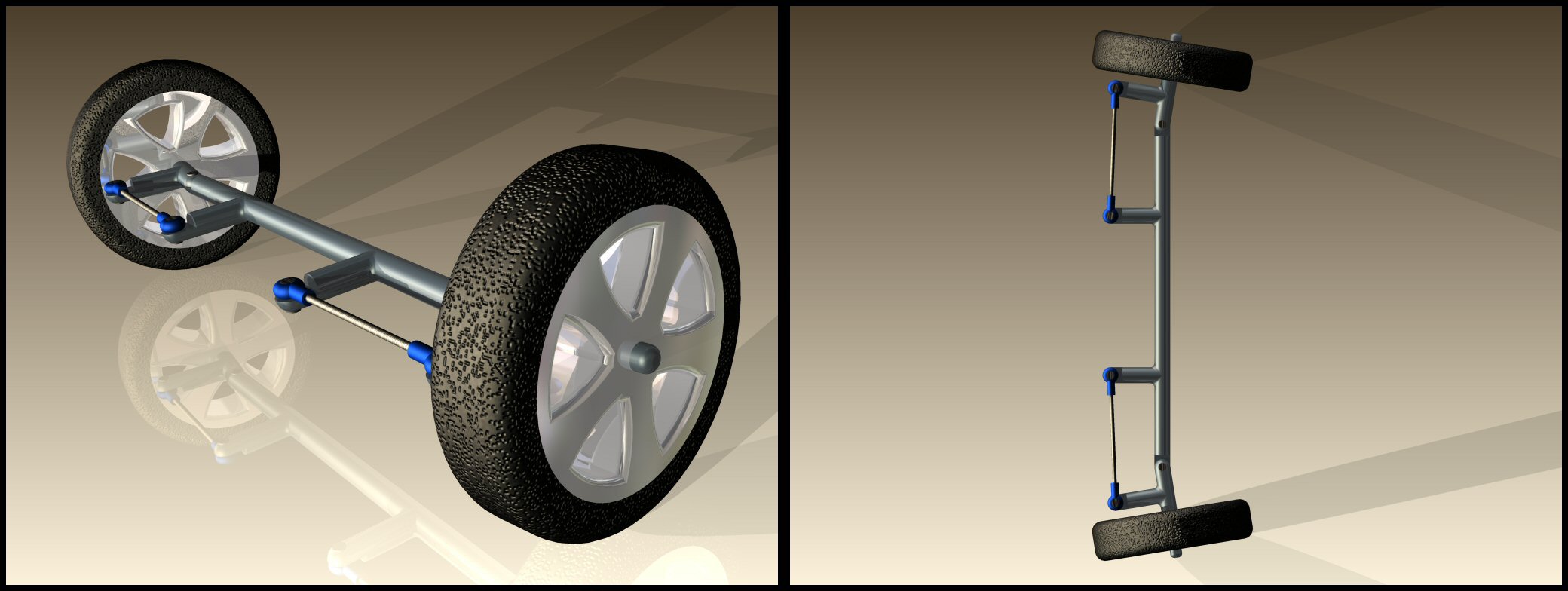

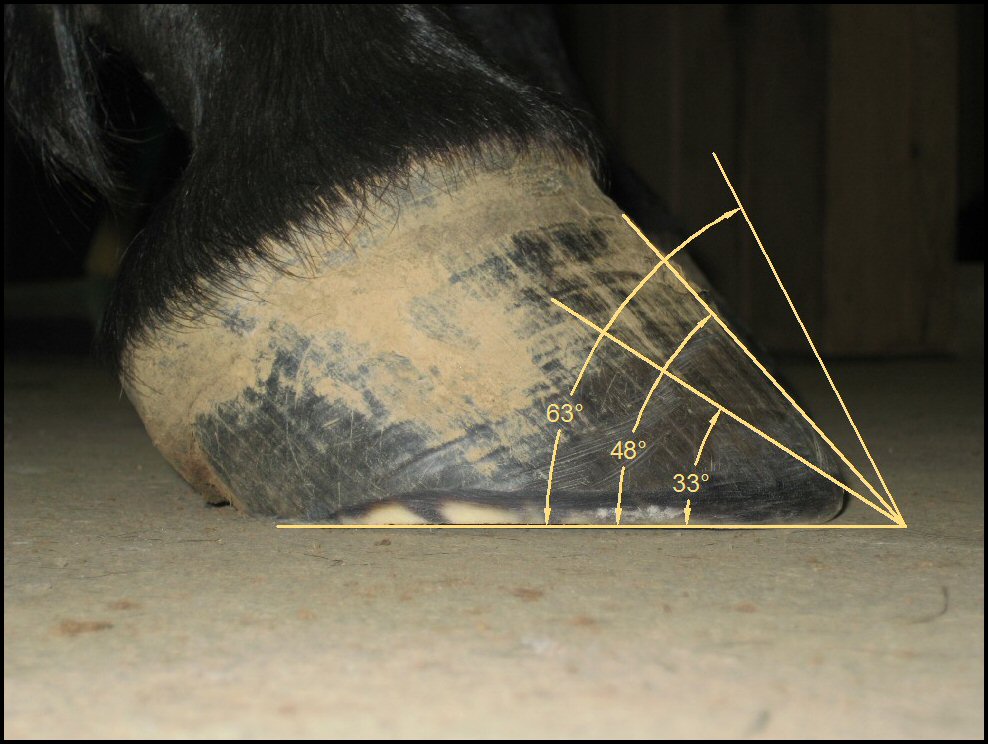

In other words, if a hoof is out of balance in the front-to-back direction (A/P balance), the weight of the horse will immediately force the foot flat to the ground at the onset of the stance phase, and the ligaments and tendons will undergo a sudden change in acceleration. This rapid change is called ‘third-order acceleration’ or ‘jerk,’ and, as Dr. Bennett states above, it stimulates the conversion of the connective tissue – ligaments and tendons – to bone. Check out A Ringbone Study above for a good look at what happens (this example shows what is usually called high ringbone, and is also a case of articular ringbone since it involves the joint), and think about the consequences of those pronounced heel-first landings so many farriers claim are ‘normal!’

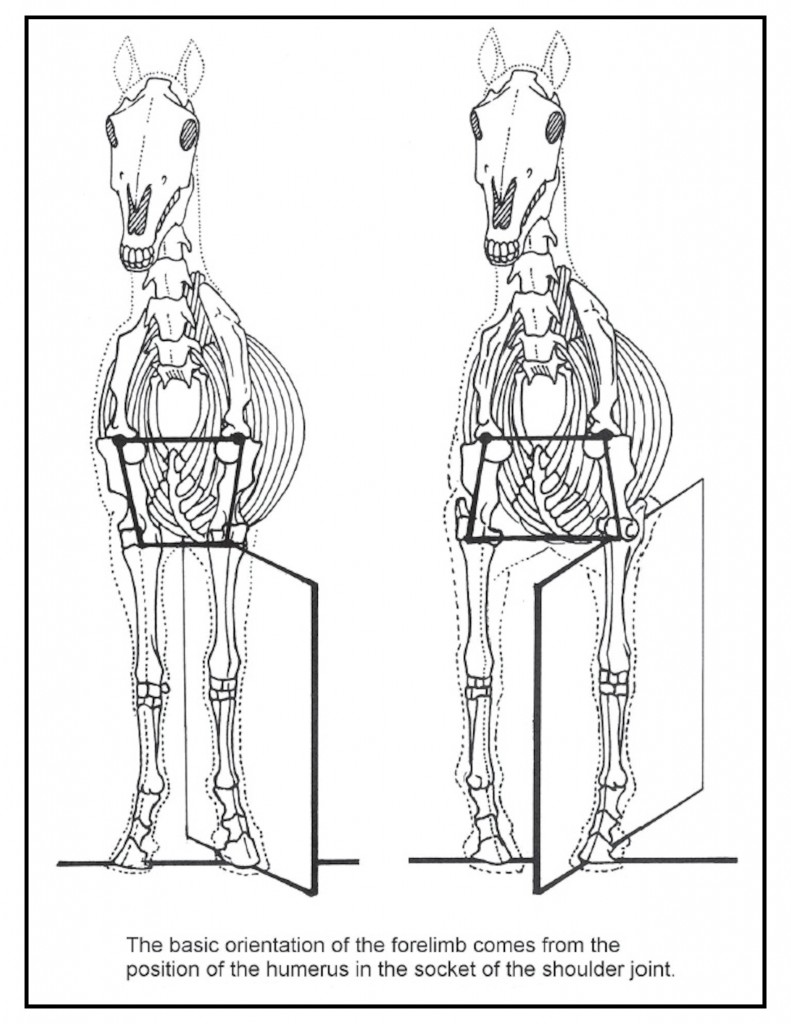

On the other hand, if the hoof is out of balance in the side-to-side direction (M/L balance), it undergoes unilateral concussion when it lands, hastening the conversion to bone of the lateral cartilage i.e. sidebone. And remember: as I pointed out in What Makes it “Natural Hoof Care?”, unilateral concussion is practically synonymous with ‘corrective farriery.’ Deliberate imbalance can never fix a conformation “problem” at the ground level, because it originates much higher in the limb – in the shoulder or hip. It can only cause long-term (and sometimes short-term) damage.

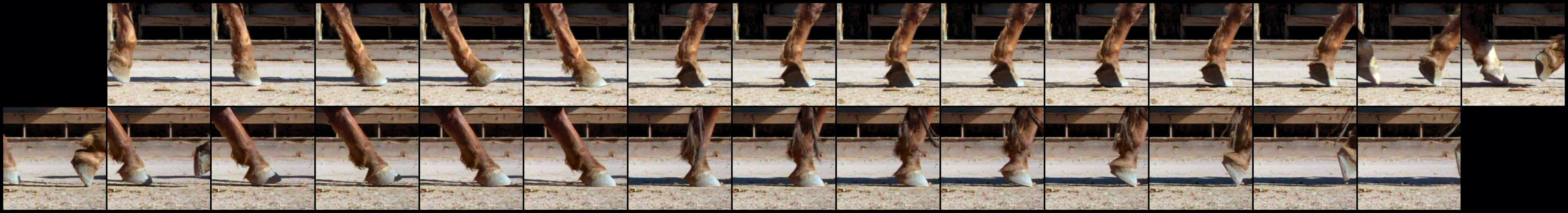

Why am I mentioning imbalance in a post about hoof angles? Because, as the last post mentioned, the horse does not adjust the flight arc of his hooves based on what’s been done to the bottom of them. So if his heels are too long (high), they’re going to hit the ground first. Likewise with toes that are too long.

For now, I’m going to leave you with the following four points:

- Hoof angle is not arbitrary; the only proper hoof angle is the one that properly aligns the bones/joints of the lower limb.

- To minimize the forces of landing – jerk and concussion – the hoof must be properly balanced.

- You cannot see a bad landing, unless it’s really bad, without the proper equipment.

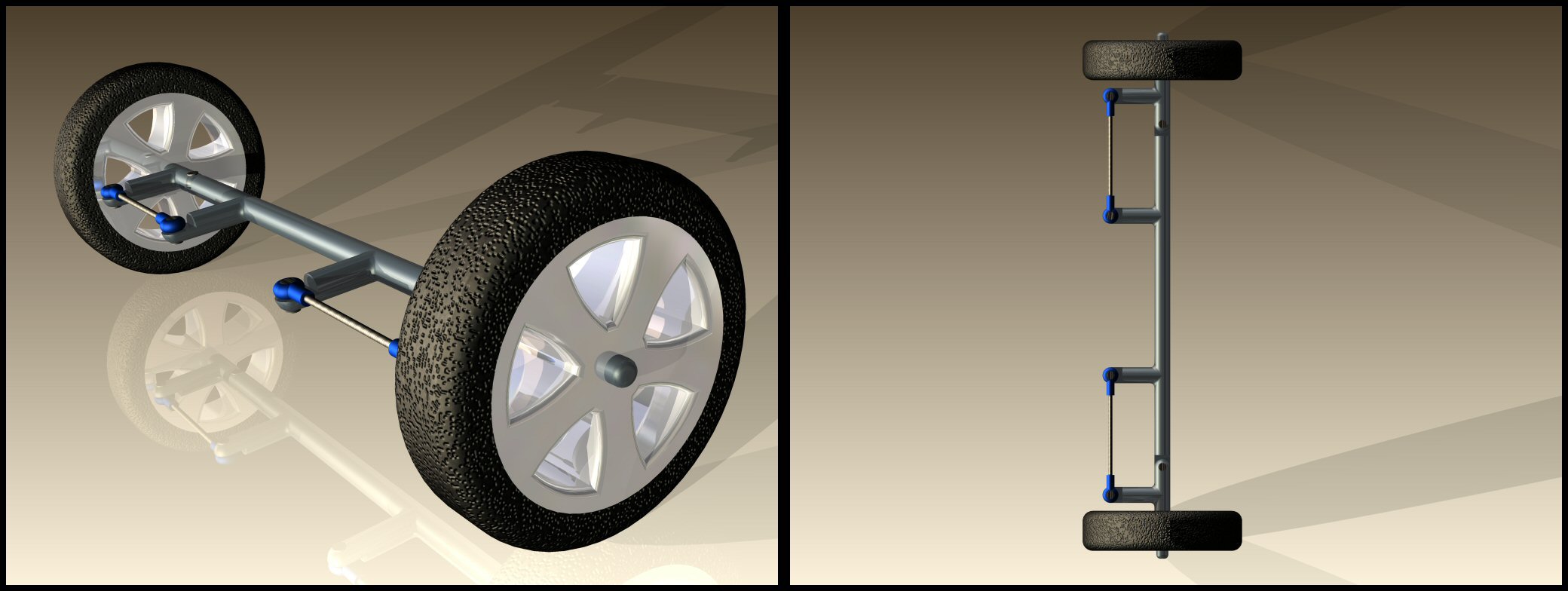

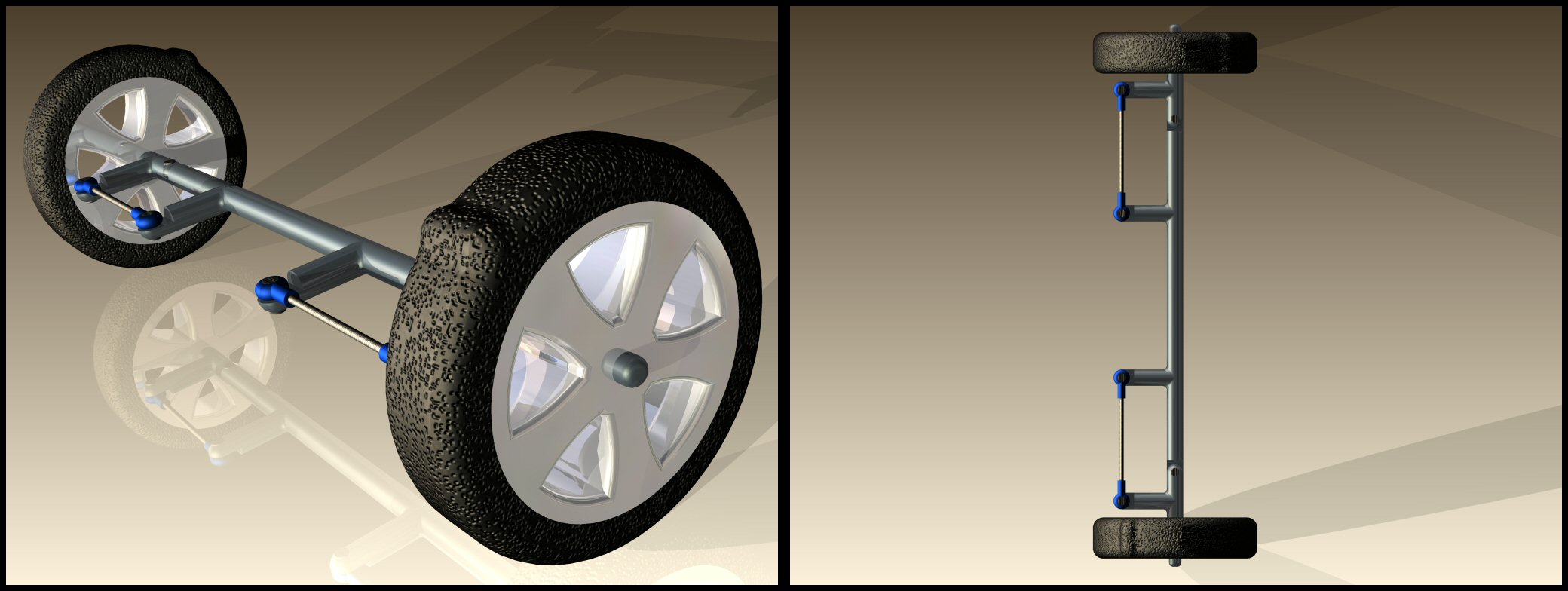

- Given sufficient movement over suitably-abrasive terrain, the barefoot horse will quickly remove any minor hoof imbalances; however, a shod horse has 0% chance of fixing his own feet.

More later…