“Once begun this disease process is irrevocable and unremittingly destructive. There is no cure, no return to normal….It is no doubt true that “cures” of navicular disease with any form of treatment reflect an incorrect diagnosis. One does not cure bona fide navicular disease.”

– James R. Rooney, DVM

Difficult words to hear and accept, to be sure, from a man who was undoubtedly one of the few in a position to make such a statement. But before losing all hope for your “navicular” horse, please keep in mind the two very important points I made in Navicular Disease – Part 1: Background and Navicular Disease – Part 2: Diagnosis:

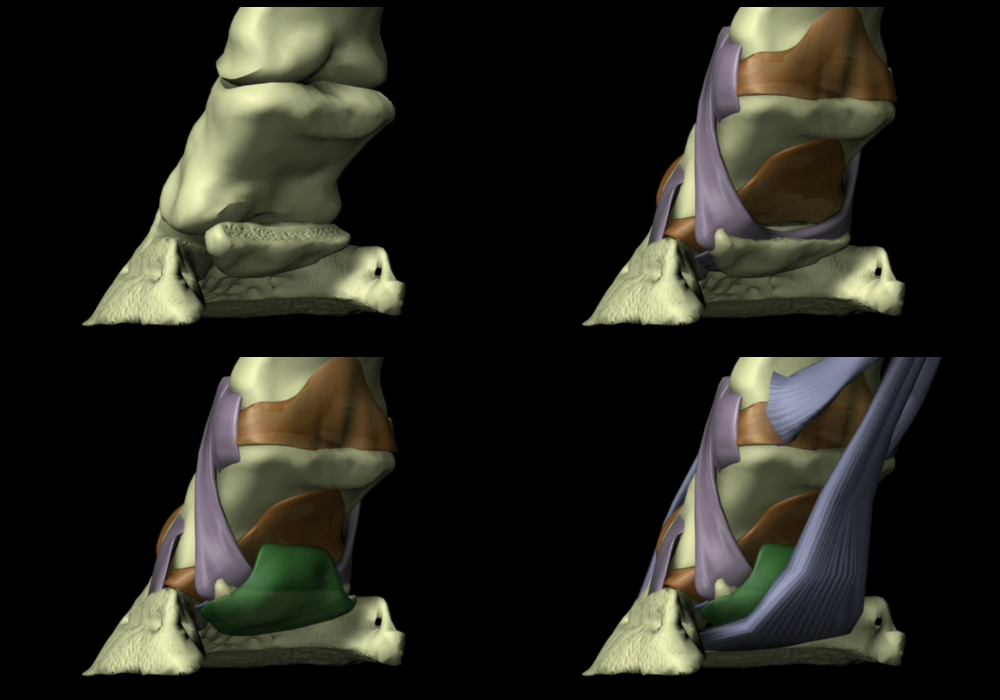

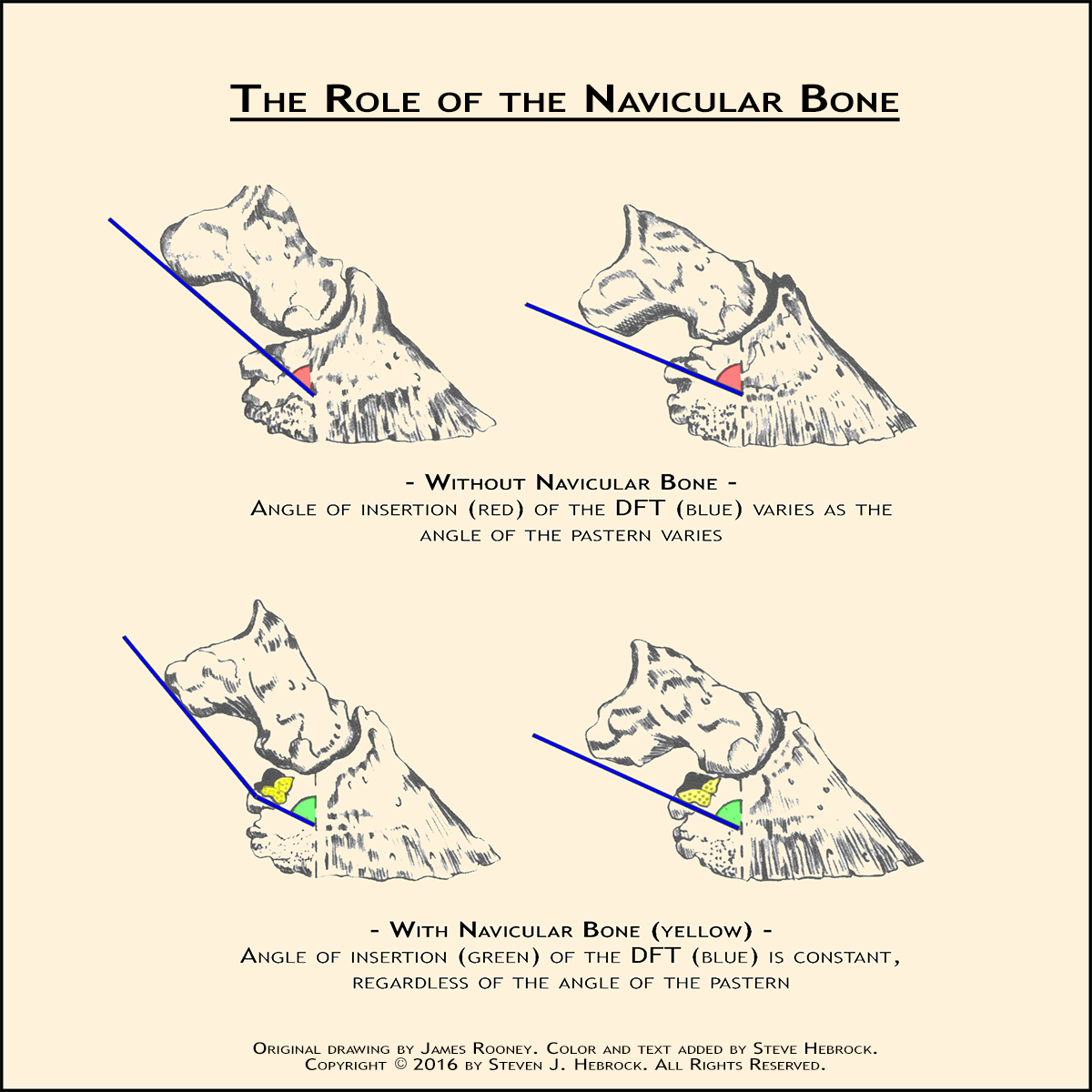

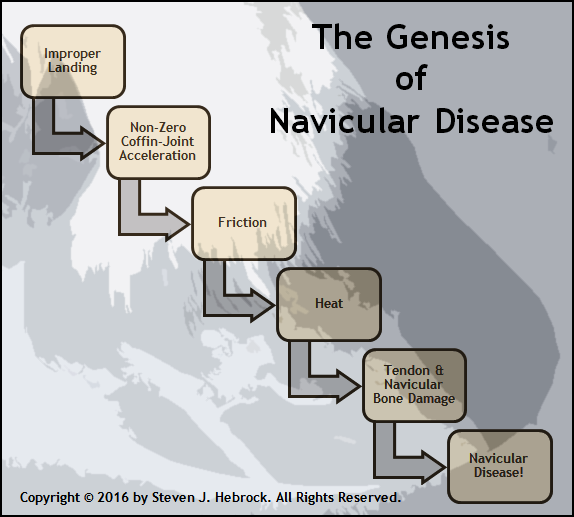

- Genuine navicular disease is damage to the deep flexor tendon and the attendant surface of the navicular bone caused by repeated heating of the tendon and bone from friction of the tendon moving across the bone, and,

- Genuine navicular disease is much less common than the very large number of (mis)diagnosed horses would lead us to believe.

Understanding and acknowledging both of these points is absolutely crucial to appreciating the existence of so many claims of “curing” navicular disease. According to Dr. Rooney, any such claim of a cure can only mean one thing: the horse in question never actually had navicular disease!

A moment’s thought will reveal why this surely must be true. While the DFT damage might, conceivably, heal if the damage to the navicular bone could somehow magically go away and not perpetuate the damage to the DFT, curing the damage to the articular surface of the navicular bone is no more likely in horses than it is in humans. Why would we see so many knee and hip replacements in people if joint damage could be undone with a dietary supplement or special shoes? Obviously, research into the treatment of various diseases is ongoing, but until someone demonstrates an effective, non-surgical approach for regenerating human cartilage and bone, I certainly wouldn’t expect to see anything that works for navicular disease in horses.

So, at least for the time being, if a horse truly has navicular disease, that damage must be considered permanent. And while it can certainly be managed to some extent, depending on the severity of the disease, it cannot be cured. So since we can’t undo what’s been done, our only viable options are to concentrate on slowing the disease’s progression and minimizing whatever pain is already present. And although I’m certainly not qualified to offer advice on pain management through drug therapy, I do want to briefly comment on one of the most commonly-prescribed drugs for “navicular” horses: isoxsuprine.

Dr. Rooney pointed out in several of his publications that the most common competing hypothesis to his evidence-based belief that navicular disease is caused by mechanical problems is that navicular disease is, instead, a vascular (blood vessel) disease. In those same publications, he also made some very compelling arguments as to why the vascular hypothesis cannot be correct. Regardless, others’ belief that the disease has vascular origins explains why isoxsuprine – a vasodilator – is so frequently prescribed. After all, if the disease is caused by blood flow problems, it might seem logical to prescribe a drug that purports to increase blood flow. Unfortunately, as pointed out in “The Effect of Oral Isoxsuprine and Pentoxyfilline on Digital and Laminar Blood Flow in Healthy Horses” (Ingle-Fehr, J.E., and Baxter, G.M., Veterinary Surgery, 28 (1999): 154-160), isoxsuprine apparently doesn’t increase blood flow in the horse’s foot! Specifically:

No statistically significant increases in DBF (digital blood flow) or LP (laminar perfusion) were detected over the 10 day treatment period with either isoxsuprine or pentoxyfilline….Neither isoxsuprine nor pentoxyfilline increased blood flow to the digit or dorsal laminae in healthy (non-laminitic) horses.

Granted, because their primary concern was with the use of these drugs in the treatment of laminitis, their study was conducted on what they determined to be laminitis-free horses without regard to other possible foot pathologies. I suppose one might argue that perhaps the drug does, indeed, work on horses with compromised foot circulation but not on normal horses, but that strikes me as highly unlikely. The researchers went on to conjecture as to why isoxsuprine appears to make some laminitic (not “navicular”) horses more comfortable, and concluded that the drug must have a very mild analgesic (pain-relieving) effect unrelated to circulation, since isoxsuprine apparently doesn’t affect blood flow.

For the “navicular” horse owner, therefore, the implications of this study are quite clear: whether or not your veterinarian believes navicular disease is caused by, or related to, circulation problems, isoxsuprine has been demonstrated to have no effect on blood flow in the equine foot. Refer him/her to the aforementioned article if he/she doesn’t believe you. Why give your horse an expensive, unnecessary, and ineffective drug? And if your horse does need relief from pain, there are far more effective and less expensive drugs readily available.

Through understanding the true cause of navicular disease comes the answer to slowing its progression: since the disease is the consequence of repeated heating of the tendon and bone from friction of the tendon moving across the bone, we must minimize the friction and consequent heating. How? Well, let’s review the list of factors that affect friction and heating from Navicular Disease – Part 1: Background:

- The degree of front-to-back imbalance in the hoof

- The stiffness of the hoof

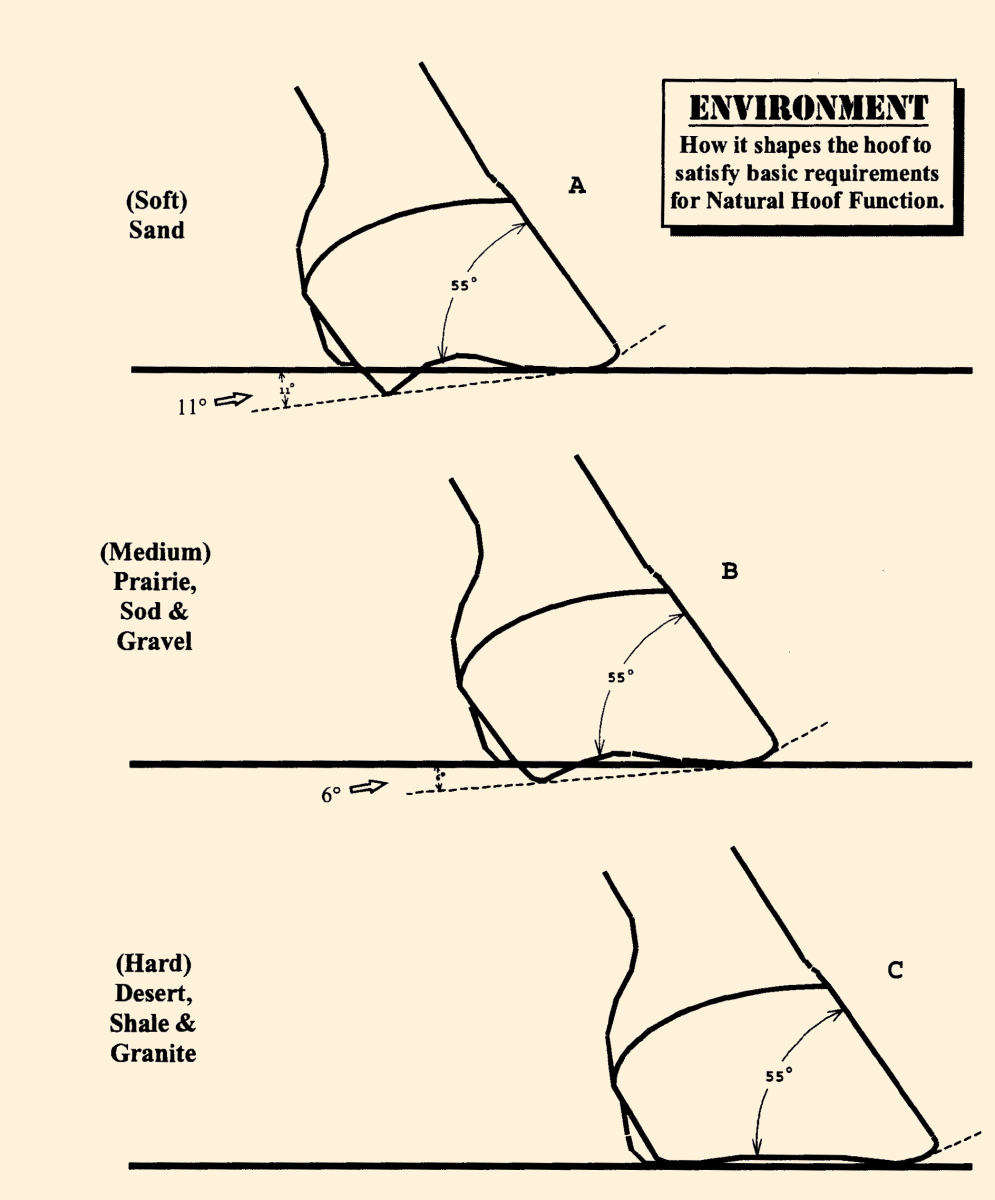

- The hardness of the terrain upon which the horse moves

- The speed at which the horse moves

- The duration of the horse’s movement

- The size of the navicular bone and deep-digital flexor tendon

Given that we’re now talking about real-world horses with less-than-optimal hoof care, we have to add yet another factor that affects the “navicular” horse:

0. The actual length of the hoof relative to its optimal length

When a hoof is properly trimmed, it will be at its shortest possible length without compromising its structural integrity or increasing its sensitivity to terrain variations. Any length in excess of this optimal length, whether from growth or from the addition of a shoe, will increase the amount of time required for the hoof to leave the ground (breakover time) during maximum DFT tension across the navicular bone. Although this probably doesn’t contribute to friction and heating, it does place more strain in the damaged area of the foot we’re trying to protect.

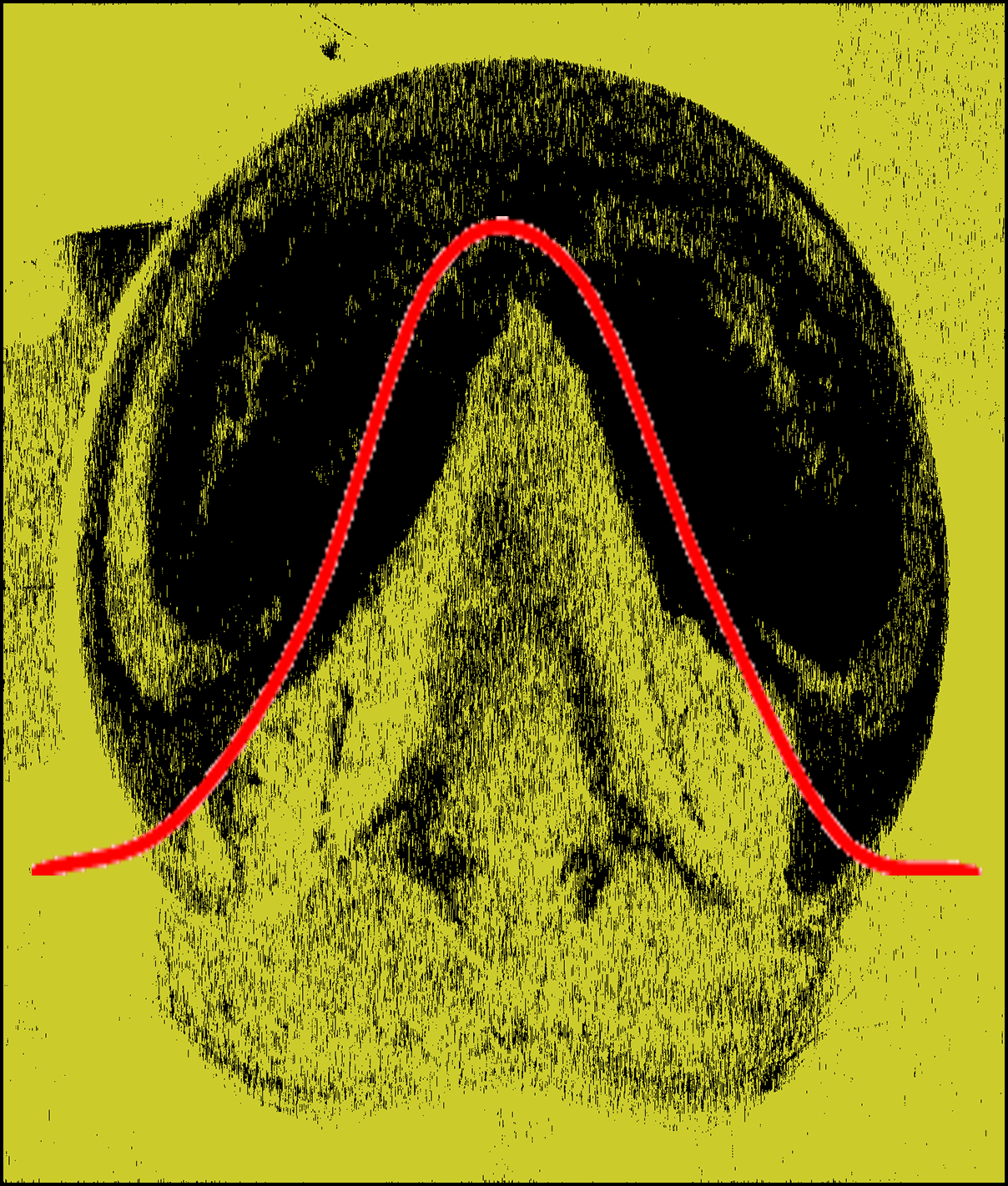

Be aware also that the common practice of using “special” shoes on these horses, such as rolled, rocker, or squared-off toes, has not been found to significantly shorten breakover time; only proper hoof length can minimize breakover time (Back, W., and Clayton, H., Equine Locomotion, (2001): 146 & 149). Note these photos of left front legs at the moment of maximum DFT tension, just before the heels leave the ground –

Adding length to these feet would only add to the time required for the hoof to leave the ground, thus prolonging the period of maximum strain across the navicular bone.

When managing the horse with navicular disease, we obviously have greater control over some of these factors than over others. For example, we cannot change the size of the horse’s bone and tendon, so number 6 can be eliminated from the onset. On the other hand, smart choices for the hardness of the terrain we ride on, coupled with how fast we ride and for how long we ride (numbers 3 through 5), can certainly minimize the amount of friction and heating of the bone and tendon. Remember: slower movement over softer terrain for shorter periods of time causes far less friction than faster movement over harder terrain for longer periods of time, just as less frequent jumps over shorter obstacles causes less friction than more frequent jumps over taller obstacles.

Far and away, though, our best opportunity for slowing the progression of the disease can be realized by minimizing numbers 0, 1, and 2 through proper hoof care. In concrete terms, that means:

- Properly trimming the horse so the hoof is optimally short and the coffin joint experiences minimal acceleration at landing i.e. a flat landing, and,

- Keeping the horse barefoot to maintain optimal hoof length, allow the foot to deform and absorb energy during initial ground contact and as it is loaded by the weight of the horse, and permit the most rapid breakover possible to minimize DFT strain across the navicular bone.

Unfortunately, these absolutely essential management measures are in diametric opposition to the advice of nearly every veterinarian and farrier. In fact, the most common advice given for the management of the “navicular” horse is the exact opposite of the above: use wedge shoes to elevate the heels and lessen the tension of the DFT across the navicular bone. While at first blush that course of action may seem logical, raising the heels of a horse makes only a small, temporary reduction in the tension of the DFT while simultaneously increasing the tension of the superficial digital flexor tendon, suspensory ligament, and extensor tendon. Much more problematic, however, especially for our “navicular” horse, is the increase in friction and consequent heating of the tendon and navicular bone that occurs with the resultant heel-first landing. In other words, elevating the heels (re)creates the very situation that caused the navicular disease in the first place!

The only situation where I could envision heel elevation as possibly being helpful to a horse with navicular disease would be if the horse were to be kept strictly on a hard, flat surface and limited to brief speeds of no greater than a walk. Think about it: if the horse were kept on a soft surface, the wedges would penetrate the surface with no net elevation of the heels, and if the horse were to move on the hard surface at any appreciable speed, the damage caused by the friction at the DFT/navicular bone interface would be greater than any benefit gained by the slight lessening in DFT tension through raising the heels.

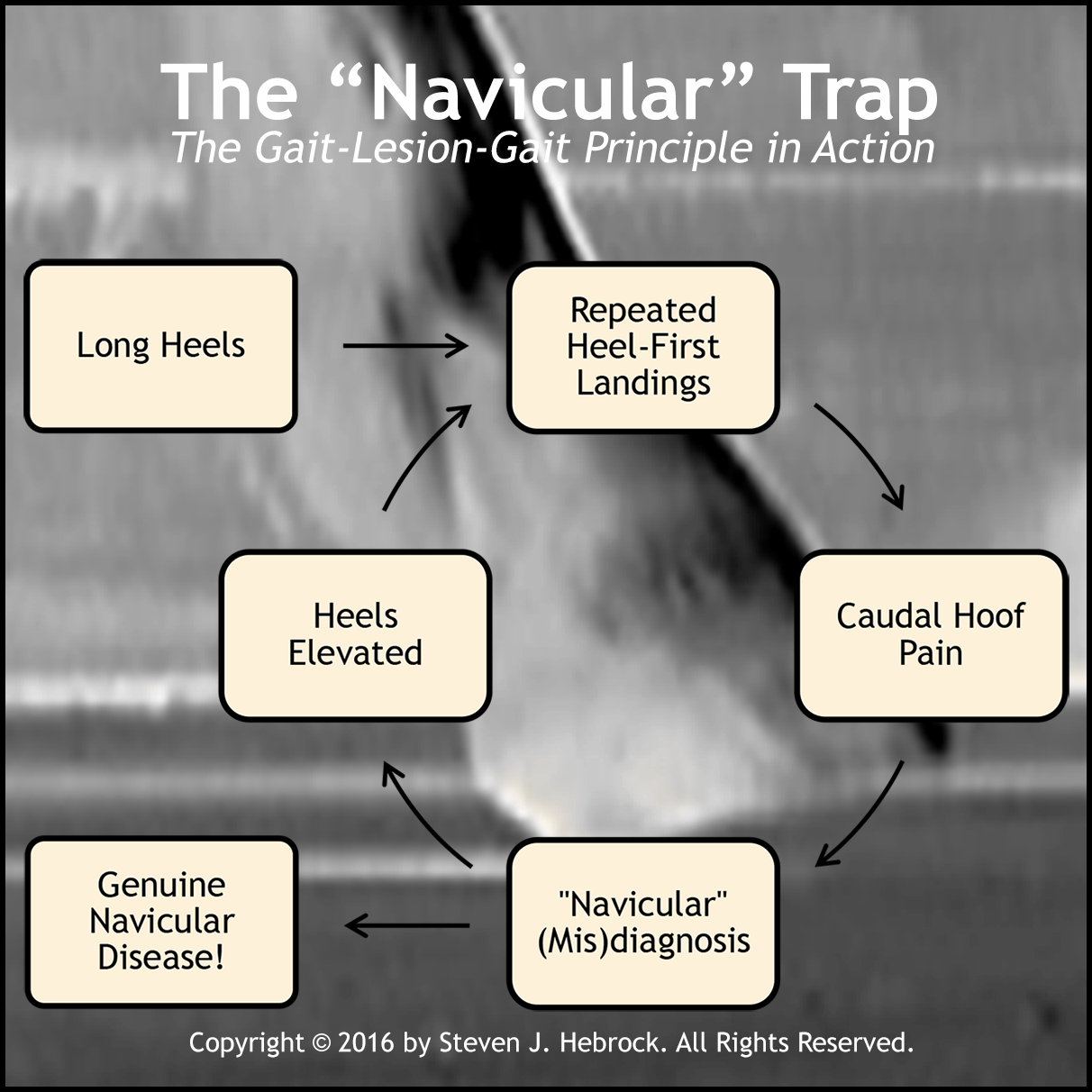

So the first priority in managing the horse with navicular disease must be stopping the progression of the disease by not doing what’s probably been done, in terms of hoof care, for the majority of the horse’s life. Because of the widely-held, but incorrect, belief that horses are “supposed” to land heel-first (see The Myth of the Heel-First Landing series for more information on why this is incorrect), the product of many – I would even say “most” – hoof care providers’ efforts are feet that are incorrectly balanced in the front-to-back (A/P) direction and therefore experience a heel-first landing. As I’ve tried to make clear through this series of articles, long-term heel-first landings are the underlying cause of navicular disease, and the problems begin when horse owners fall into what I’ve termed “The ‘Navicular’ Trap” –

Here’s how it usually plays out:

- The horse’s (front) heels are left too long by the hoof care provider

- As a result of working on harder ground, the horse becomes heel-sore from repetitive pounding

- The vet or hoof care provider diagnoses “navicular,” and raises the heels to allegedly reduce pain

- The horse becomes increasingly heel-sore because of increased pounding

- As a consequence of the repeated friction and attendant heating at the DFT/navicular bone interface, the horse ends up developing genuine navicular disease

This is a perfect illustration of the so-called gait-lesion-gait principle in action. As Dr. Rooney phrased it in his Biomechanics of Lameness in Horses –

The gait abnormality caused by a specific lesion is the gait abnormality which will cause the lesion.

What does that mean? Well, I interpret it like this: if a horse (or anything else) is forced to move in a manner that mimics the gait of a particular pathology, continued movement in that manner will eventually cause the very pathology the gait is indicative of! Specifically, if a horse’s heels are left too long for too long, he will become heel sore and his stride will be foreshortened (a temporary gait abnormality indicative of navicular disease). If his heels continue to be left too long – or worse, are further elevated with wedges – he may eventually develop navicular disease (the lesion), which will then cause permanent heel pain (and a permanent gait abnormality).

So preventing navicular disease and managing the horse with existing navicular disease are actually one and the same process: ensure the horse is experiencing minimal coffin-joint acceleration to the extent possible, using the guidelines above. By doing so, both the sound horse and the “navicular” horse will be moving with minimal resistance and (therefore) maximal efficiency, giving him the best chance possible at long-term comfort and soundness. And that’s the goal!

To reiterate the most important points of this series of articles:

- True navicular disease is damage to the deep flexor tendon (DFT) and the attendant surface of the navicular bone.

- Navicular disease is the result of repeated heating of the DFT and navicular bone surface caused by the friction resulting from non-zero-acceleration coffin-joint landings i.e. toe-first or heel-first landings.

- While it definitely does exist, instances of true navicular disease are far less prevalent than commonly believed.

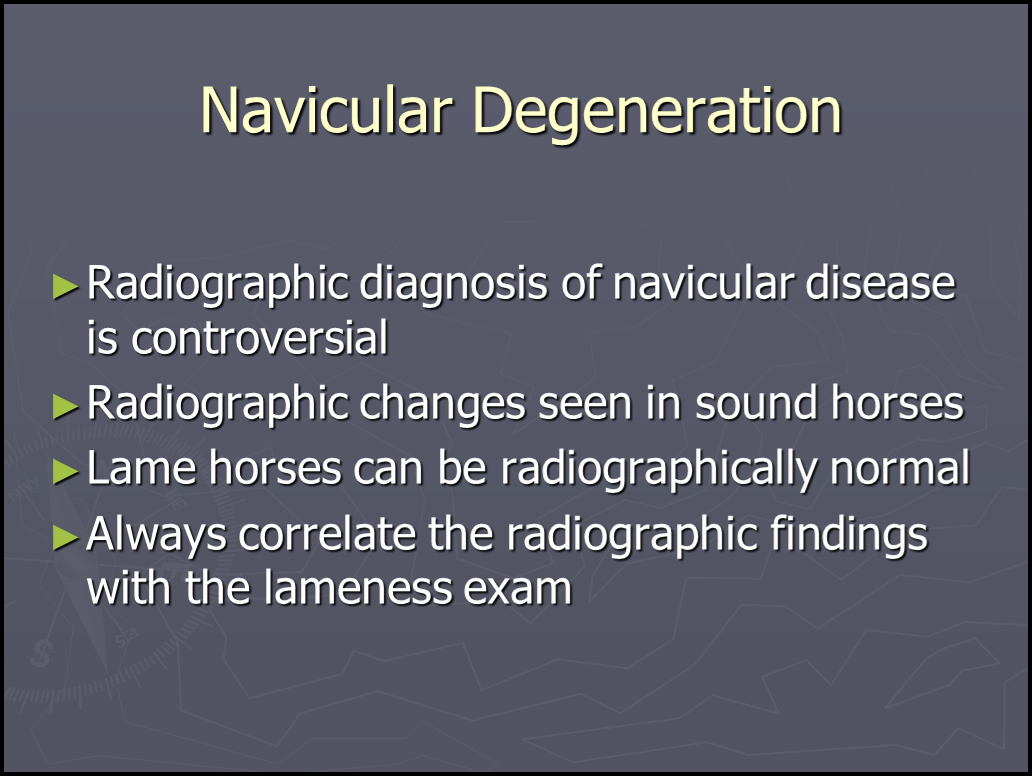

- Diagnosing navicular disease cannot be done via radiographs unless the disease is already in its advanced stages, and instead is best diagnosed with MRI or less accurately with a combination of techniques including a thorough patient history.

- True navicular disease cannot be cured.

- The two most common treatments for navicular disease – isoxsuprine and wedge shoes – are ineffective (isoxsuprine) and cause further damage (heel wedges).

- Effectively managing navicular disease and preventing navicular disease both depend on minimizing the underlying cause of the disease (friction) through proper hoof care, which means an optimally-short hoof experiencing a flat landing at the walk.

Above all, don’t lose hope if your horse is diagnosed with “navicular;” in my experience, odds are he doesn’t really have it! It’s much more probable he’s sore from excessive heel length, bad side-to-side balance (i.e. “corrective trimming”), sheared heels from radically different heel lengths, or an infection in his frog – all problems related to improper hoof care. Carefully consider his history and symptoms as well; your halter horse or brood mare isn’t a likely candidate for navicular issues, and a diagnosis of “navicular” in a single front foot or hind feet is probably not correct, either. Find someone who truly understands what proper hoof care is all about (admittedly challenging!), and allow him/her to help you rule out other far more likely possibilities.

In wrapping up this series, please allow me to make just one more point: I’m well aware that much of what I’ve presented – indeed, much of what I present on a variety of subjects, not just on navicular disease – flies in the face of popular thinking and advice. But what it absolutely doesn‘t fly in the face of is logic. If you’ll set aside your beliefs and carefully consider the evidence I’ve presented, I think you’ll agree…