Thanks to COVID-19, most of us probably aren’t spending much time in restaurants these days. But many of our horses, on the other hand, may nevertheless be spending more time eating higher-calorie food than they should be! Yes, I realize I’m not an equine nutritionist, and I don’t pretend to be one. But I have spent a fair amount of time studying enough of the basics of equine nutrition with Dr. Jessica Bedore, my former equine nutritionist colleague at The Ohio State University, to feel competent talking about how to determine proper caloric intake.

My decision to discuss it now is being driven by three things: 1) the ever-increasing number of overweight horses we encounter on a daily basis, 2) the apparent lack of knowledge by horse owners and barn managers about how to determine how much a horse should be eating, and 3) the usual annual increase in the incidence of laminitis in the area because of the rapidly-growing (and sugar-laden) grass. And because truly comprehensive hoof care involves a great deal more than just proper hoof trimming (which, by the way, is why we spend a tremendous amount of time discussing other contributing factors to hoof quality and form in the Liberated Horsemanship Gateway Clinics), I feel compelled to share this knowledge in a sincere effort to help horses avoid the health issues that result from obesity.

Yes, I’m well aware many people find the idea of having to do any sort of calculations intimidating and even frightening. But the good news is the math we need for diet planning is extremely simple and straightforward, and can be done by anyone using even the lowliest of calculators, including the one on your phone. So let’s get started!

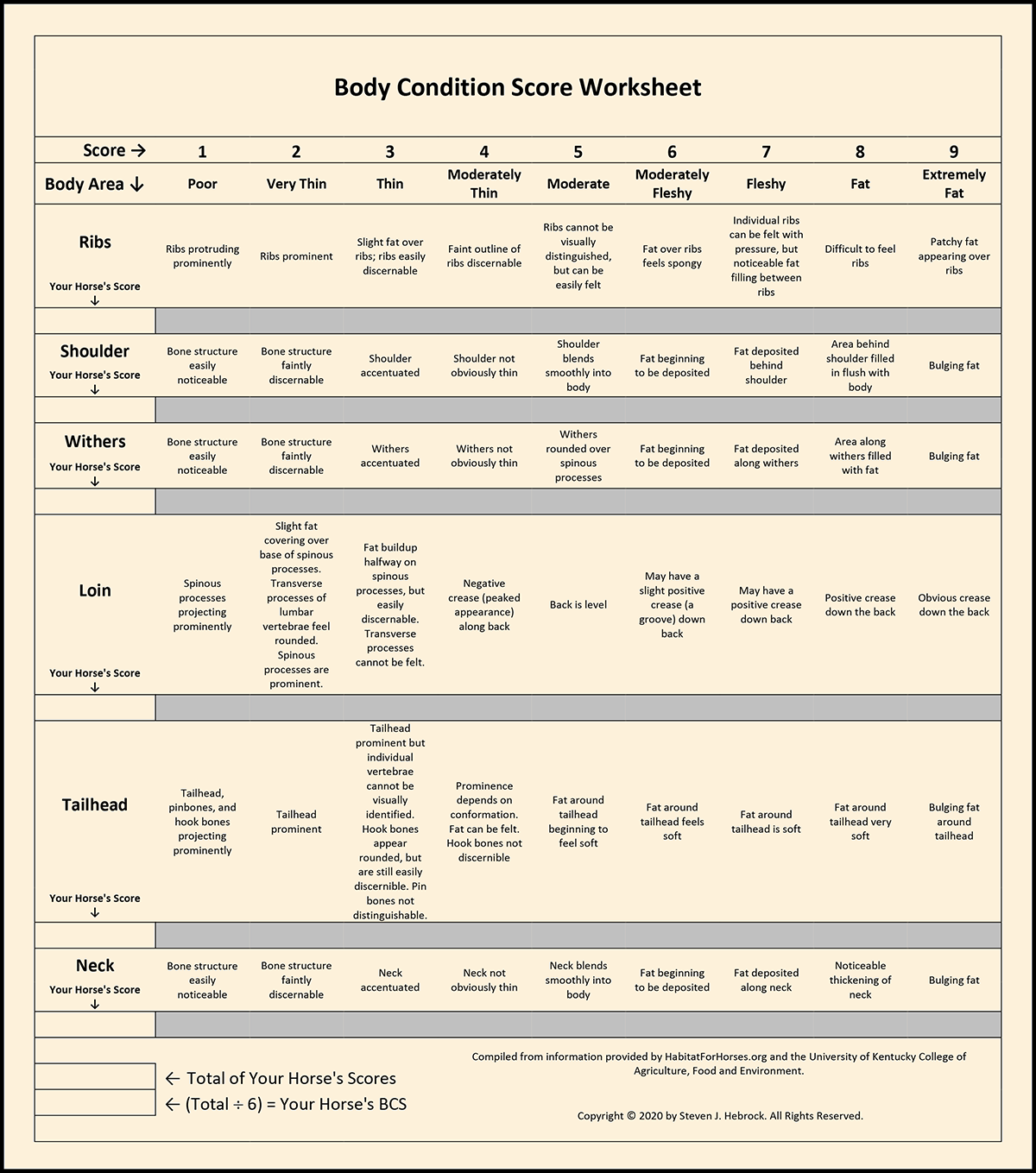

Part 1 of this series is aimed at teaching you to recognize whether your horse is too fat, too thin, or just right, and how to calculate how many calories per day he needs to maintain a proper weight. Probably the most standardized way of starting this process is to figure out your horse’s Body Condition Score, or BCS. This method of assessing the amount of fat on a horse’s body was developed in 1983 by Dr. Don Henneke at Texas A&M University, and the Henneke System has become the de facto standard for describing a horse’s condition.

For many, this will undoubtedly be the most difficult part of our task, simply because we horse owners can’t seem to look at our horses with an unbiased eye. But there’s no upside to convincing ourselves that our horse isn’t overweight if, in fact, he is – only a potentially horrible downside. Just make certain whoever does the evaluation is as objective as possible: someone with a discerning eye who’s willing to put aside all feelings and opinions and honestly assess your horse. And if you or your chosen evaluator isn’t reasonably familiar with the process of calculating BCS, I strongly suggest you both familiarize yourselves with this very useful process; you can find a good step-by-step article on Body Condition Scoring here, although there are a number of articles and video guides available. To help you with the actual process of Body Condition Scoring your horse, I’ve created the following worksheet and guide –

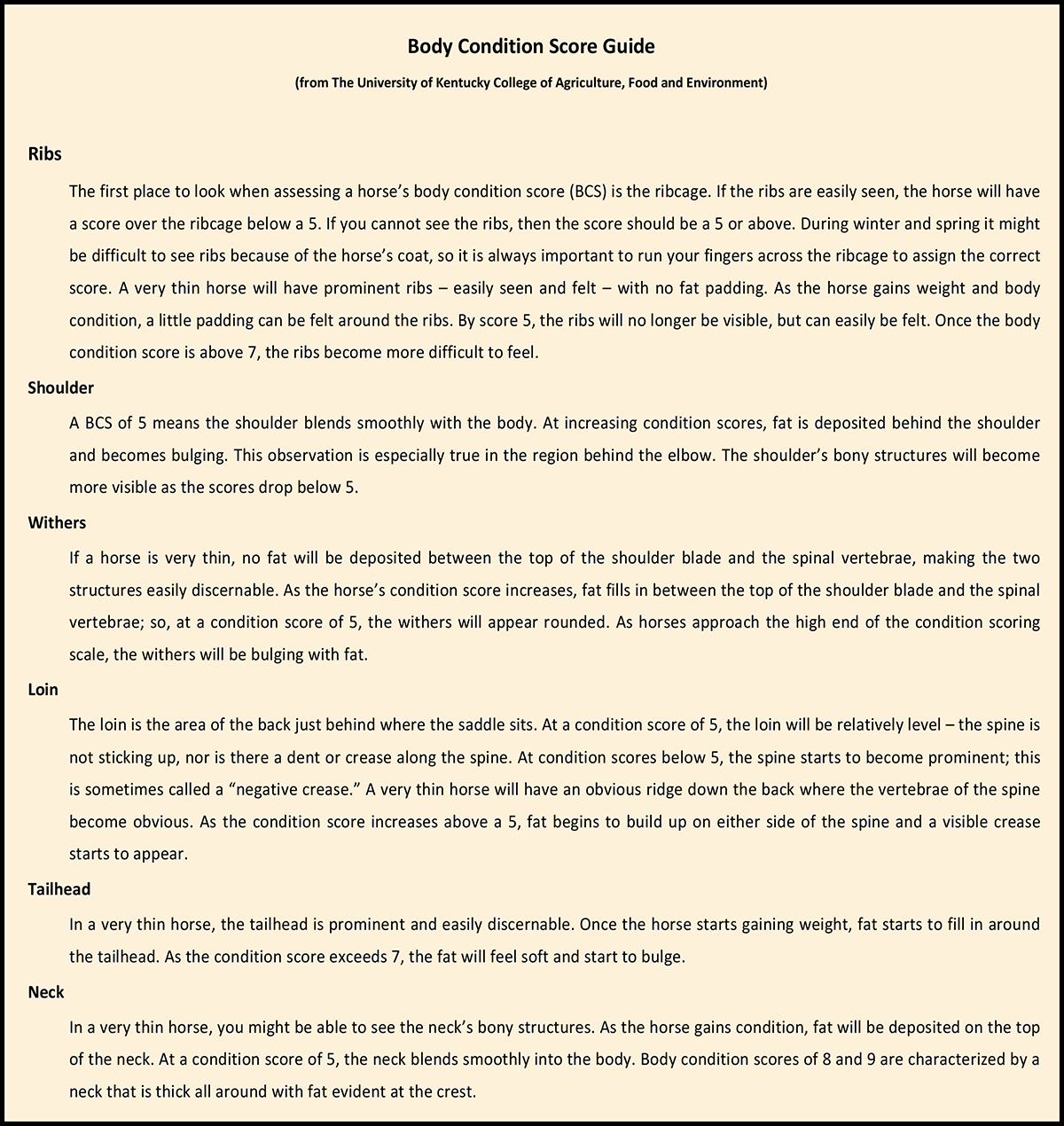

Incidentally, to make all this information a bit easier to read, use, and share with others, I’ve created a PDF file containing all of the tables, charts, and worksheets in this article for downloading and printing here!

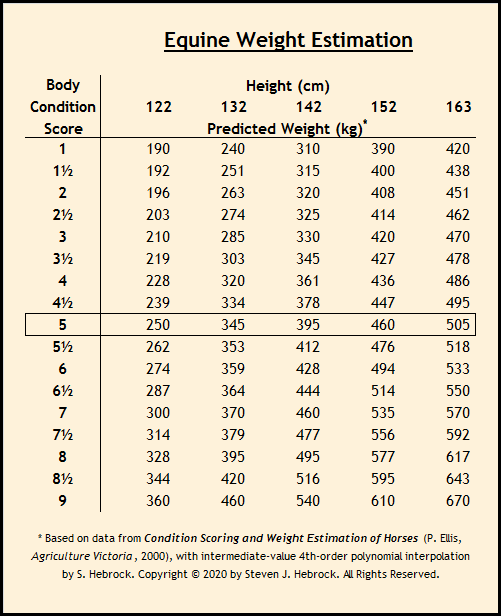

Once you’ve determined the BCS, the next step is to find out how much weight your horse needs to lose or gain. The following chart should help; just look up your horse’s BCS in the column under his height, and compare it to the weight given for the same height with a BCS 5. For example, a 15-hand horse with a BCS 6.5 (extremely common, in my experience) has an approximate weight of 1,133 pounds and a target weight of 1,014 pounds; therefore, he needs to lose about 119 pounds. Of course, these are approximations, and are presumably based on average-build i.e. riding horses. But the numbers should be accurate enough to give you a solid feel for how much weight change your horse requires. This table is in hands and pounds –

This is the metric version, with the hands heights converted to centimeters and the weights in kilograms –

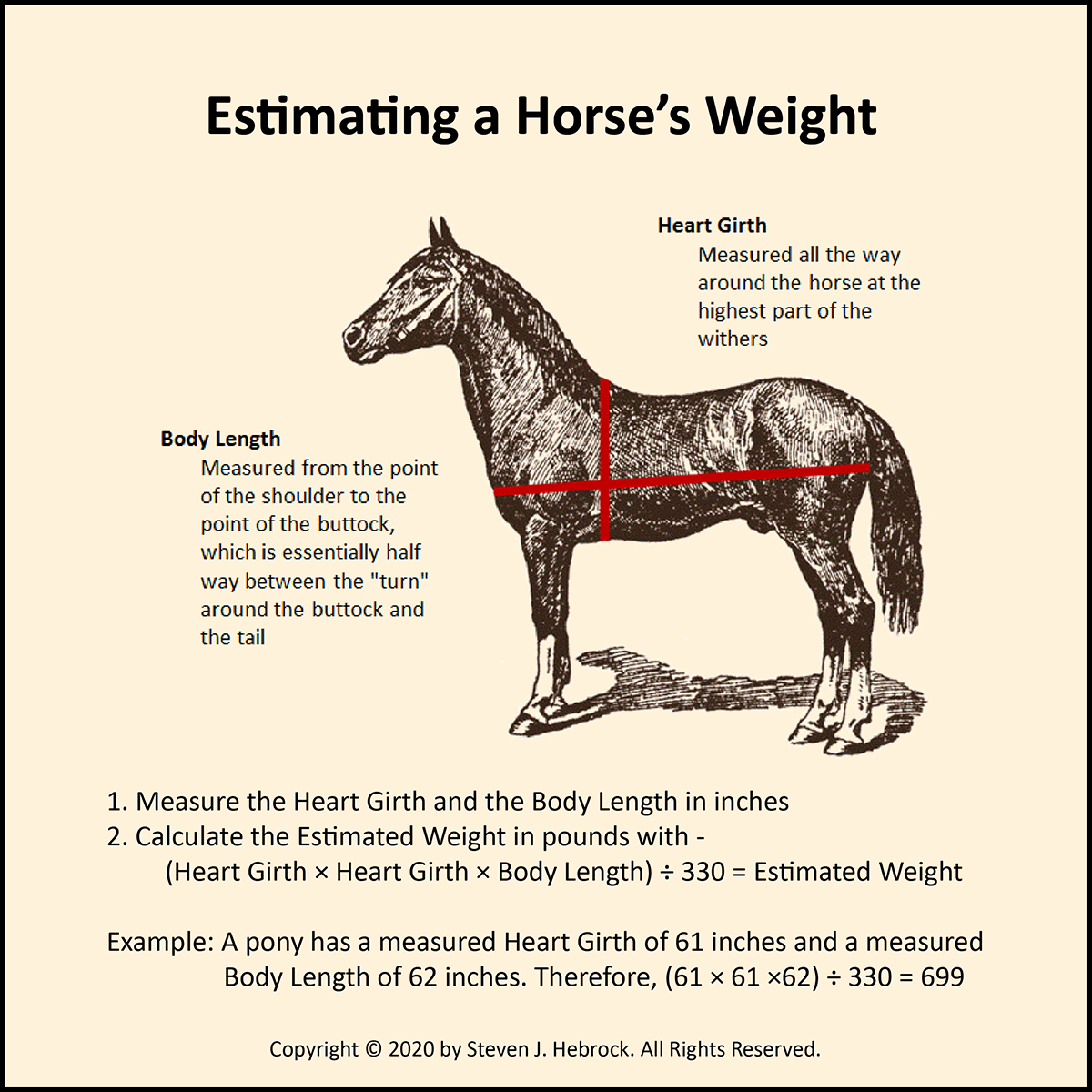

At this point you may be wondering why we don’t simply use the ubiquitous weight tape instead of bothering with figuring out the horse’s BCS. A couple of reasons: 1) we know weight tapes aren’t particularly accurate, and 2) we want to actually look at the horse’s body fat to assess his condition, and not base our diet decisions solely on a string of numeric approximations. Still, the weight tape is a useful tool when it comes to tracking changes in our horse’s weight, so knowing what your horse weighs in addition to calculating his BCS is useful. However, Texas A&M University has developed a far more accurate method of estimating a horse’s weight than with a weight tape, using an ordinary cloth tape measure and some simple math as described below. I’ve discovered, by the way, that most of us will need some assistance to measure the Body Length on the average-sized riding horse; my arms just aren’t that long!

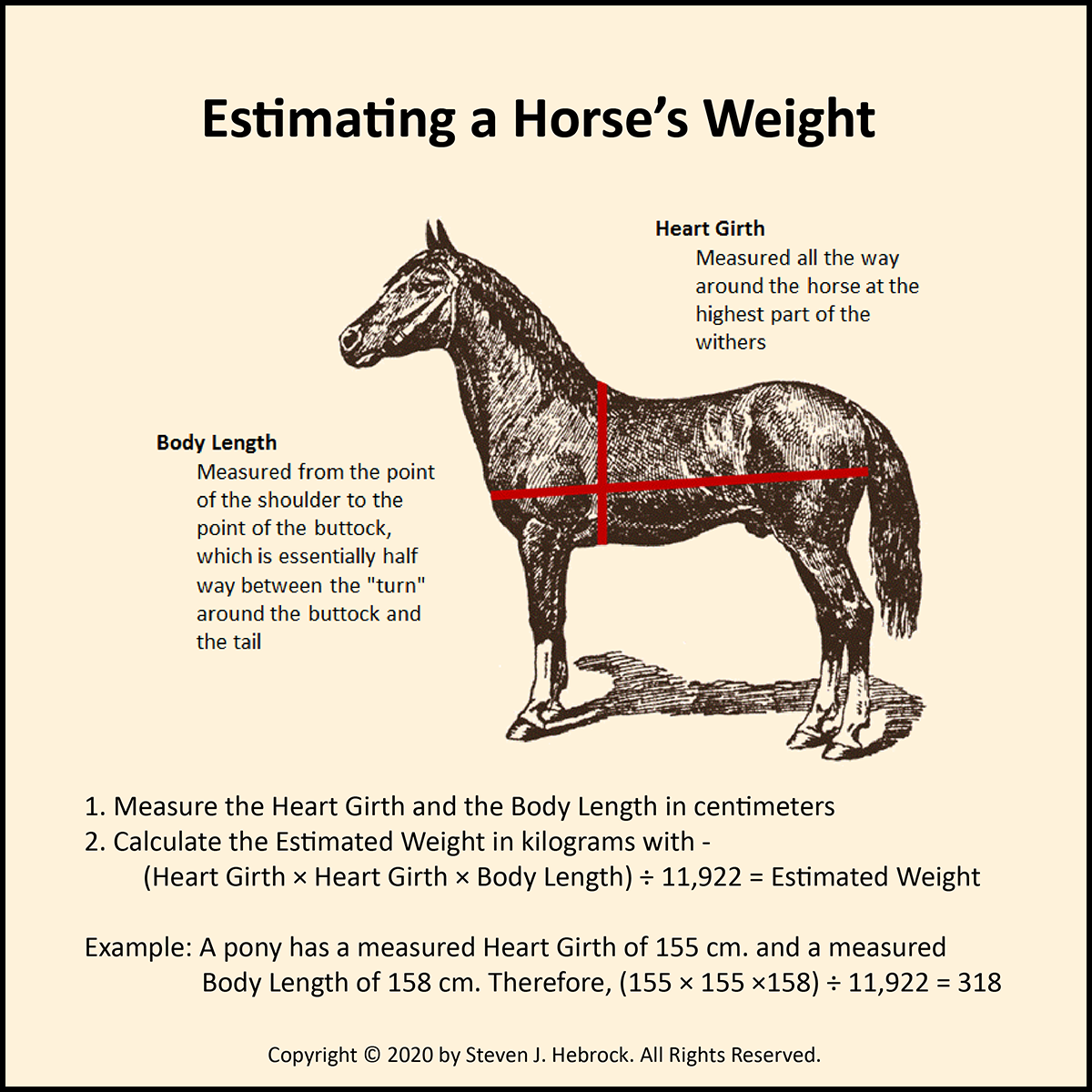

Again – here’s the metric version, with lengths in centimeters and weight in kilograms –

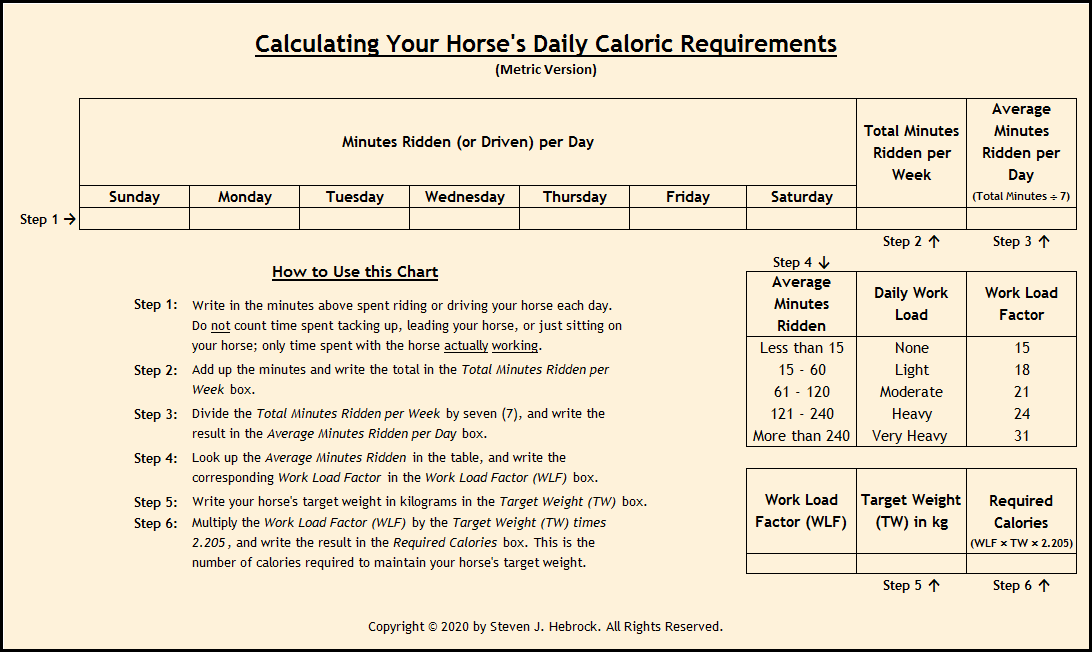

So you now know approximately how much your horse weighs, and how much he should weigh. Now it’s time to figure out how many calories per day are necessary for your horse to maintain his target weight, which is probably not his current weight. And just as with the BCS, determining caloric requirements requires you to be absolutely honest about how much you actually ride (or drive) your horse, because the amount of work he does is key to calculating caloric needs.

This is really the easiest and most straightforward part of the process; all we need is some accurate information about your riding or driving habits. You’ll need to collect some information about how much you ride, and then do some simple calculations using the worksheet below to figure out how many calories per day your horse needs to maintain his target weight –

Here’s the metric version, with the target weight in kilograms –

As an example, suppose I ride my 15-hand horse with a target weight of 1,014 pounds for 20 minutes every Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday, and Sunday. Just for the record, I’ve not counted the 10 minutes it takes to collect my horse from the pasture, the 10 minutes it takes to clean and tack him up, the 5 minutes each of a leisurely warm-up and cool-down walk, or the 10 minutes to get to and from the arena and untack and put him away when I’m done. So, following through the worksheet:

Steps 1 & 2 –

20 + 20 + 20 + 20 = 80 Total Minutes Ridden per Week

Step 3 –

80 ÷ 7 = 11 Average Minutes Ridden per Day

Step 4 –

11 = Less Than 15 = 15 Work Load Factor

Steps 5 & 6 –

15 x 1,014 = 15,210 Required Calories per Day

And now we know how many calories our horse needs to maintain a healthy weight! So take an objective look at your horse’s body and your riding or driving patterns, and figure out how many calories your horse should be consuming in preparation for the second part of this series.

In the next installment, we’ll discuss the potential challenges of selecting appropriate types and amounts of forages and feeds to meet, but not exceed, this requirement. Why will it be challenging? Primarily for two reasons: 1) in the case of forage, the calorie content of all of them, including green grass, varies by a number of factors, including forage type, maturity when cut or consumed (in the case of green grass), time of day when cut or consumed, moisture content, and storage conditions, and 2) in the case of feeds, manufacturers don’t generally publish the calorie content of their products so you have to directly contact the company to get the information you need to plan the diet. But in spite of all these apparent obstacles, it’s fairly easy to ensure your horse is getting adequate, but not excessive, calories.

All for now…