I realize this may seem to some like a radical departure from my usual articles about hoof care, but since the subtitle of the site is, after all, “Better Horse Management through Science,” I thought it appropriate to weigh in on a common situation I see in barns every summer. And that’s the one where people are trying to use fans – usually a lot of them – in what I see as a largely futile attempt to cool the barn. Here’s a photo of a typical fan arrangement in a horse barn. Note not only the box fans on each stall, facing inward, but the large fan on the floor and the blower on farther down the aisle. And yes, that’s my horse Andy wondering what I’m doing!

So what’s wrong with this setup? Well, several things. Cooling takes place when a body loses heat by transferring it to cooler molecules, either directly to cooler air, or indirectly to perspiration and then to cooler air. Think of it like this: heat always moves from higher temperatures to lower temperatures, which means you don’t (can’t) “add cold” to an environment, but can only “remove heat.” So for cooling to occur, the surrounding air temperature has to be cooler – and ideally, drier – than the horse. The greater the difference in temperatures, the more rapidly heat will move. And it’s also important to note that cooling a horse isn’t like cooling a pie, because a horse’s body is constantly converting food to (heat) energy and we’ve got to stay ahead of that conversion in order to effectively cool him.

When moving air passes by an object, a couple of things happen. First, if the object is warmer than the moving air, the warmer object will give up heat to the cooler air, making that “chunk” of air warmer. That’s why the air needs to move – a new chunk of cooler air must take its place for the heat transfer to continue, or the air and the object will be at the same temperature and no cooling will take place. And second, if the object is wetter than the moving air, some of the moisture will evaporate and heat will once again be transferred to the air. And as in the first situation, a new chunk of drier air must replace the now-wetter air for the process to continue. When a living, perspiring being is the object in this second situation, this cooling effect is perceived as being greater than it actually is because the being’s body is constantly attempting to maintain its surface temperature. This perceived effect is referred to as wind chill.

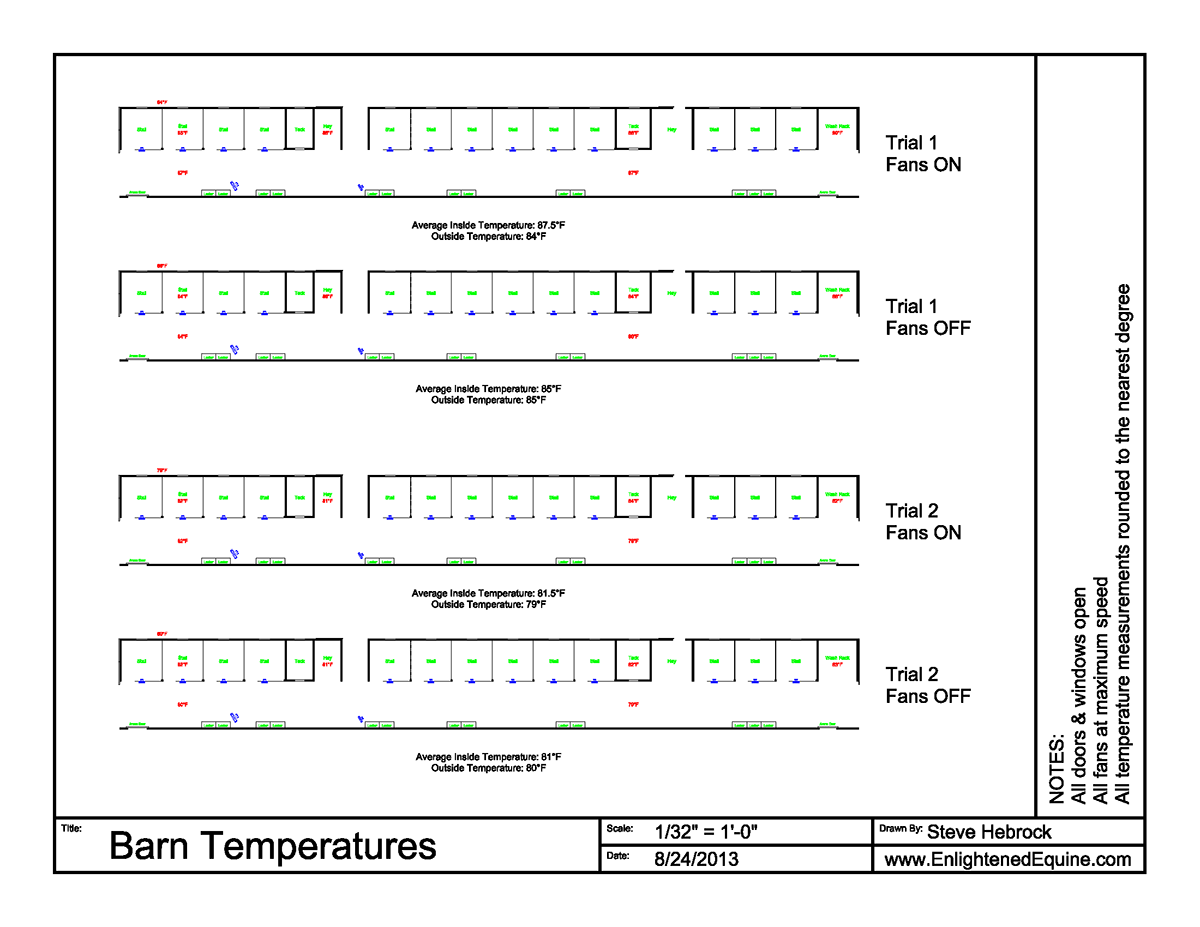

Blowing air in the general vicinity of a horse, consequently, does very little actual cooling because the air doesn’t really “go” anywhere; it simply wraps around the fan and transfers its heat and moisture to the other air in the vicinity. So, very quickly, you reach a state of equilibrium in which all you’re doing is recirculating high-temperature, moisture-laden air. The vast majority of cooling that seems to be occurring is really only because of wind chill, and not because of any actual significant temperature reduction. That also means the fans not aimed directly at a horse or a person aren’t doing anything at all other than recirculating the same small amount of air over and over again. Check out the following diagram of the barn aisle in the photo above, with the temperatures measured in the seven locations indicated both with and without the fans running –

Notice anything? It would probably shock most barn owners to see that the inside temperatures, at least in these two sets of measurements, were closer to the outside temperatures with the fans off! That means in spite of moving literally tens of thousands of cubic feet of air per minute, not to mention spending money to do it, you’re actually making the situation worse with the fans rather than better.

So is trying to cool a barn really a no-win situation? Not at all. Horse people just seem to go about it the wrong way, and ought to take a cue from many livestock barns. To effectively cool the barn, which, unless you’re willing to invest in some sort of refrigeration system means lowering the barn temperature & humidity to match the outside air temperature & humidity when it’s cooler outside, you have to replace the air in the barn. And it’s a lot easier and less expensive to do than you might think. It’ll also lower your electricity costs, labor costs, and risk of fire.

You begin the process by understanding that in order to really move air, you have to use a fan properly. A fan is, in effect, an air pump, and works by decreasing the pressure on one side of it while increasing the pressure on the other side. When it’s just sitting in space, there isn’t anything separating the lower-pressure side from the higher-pressure one, so the actual air movement any distance from the fan is very small. It’s like trying to fill a balloon with water by aiming a hose at it from several feet away. You might manage to get a little water into it, but it certainly isn’t going to make a big splash! So just as we can make filling the balloon much more efficient by keeping the water pressure confined to only the inside of the balloon, we can greatly increase the efficiency of a fan by separating its inlet from its outlet.

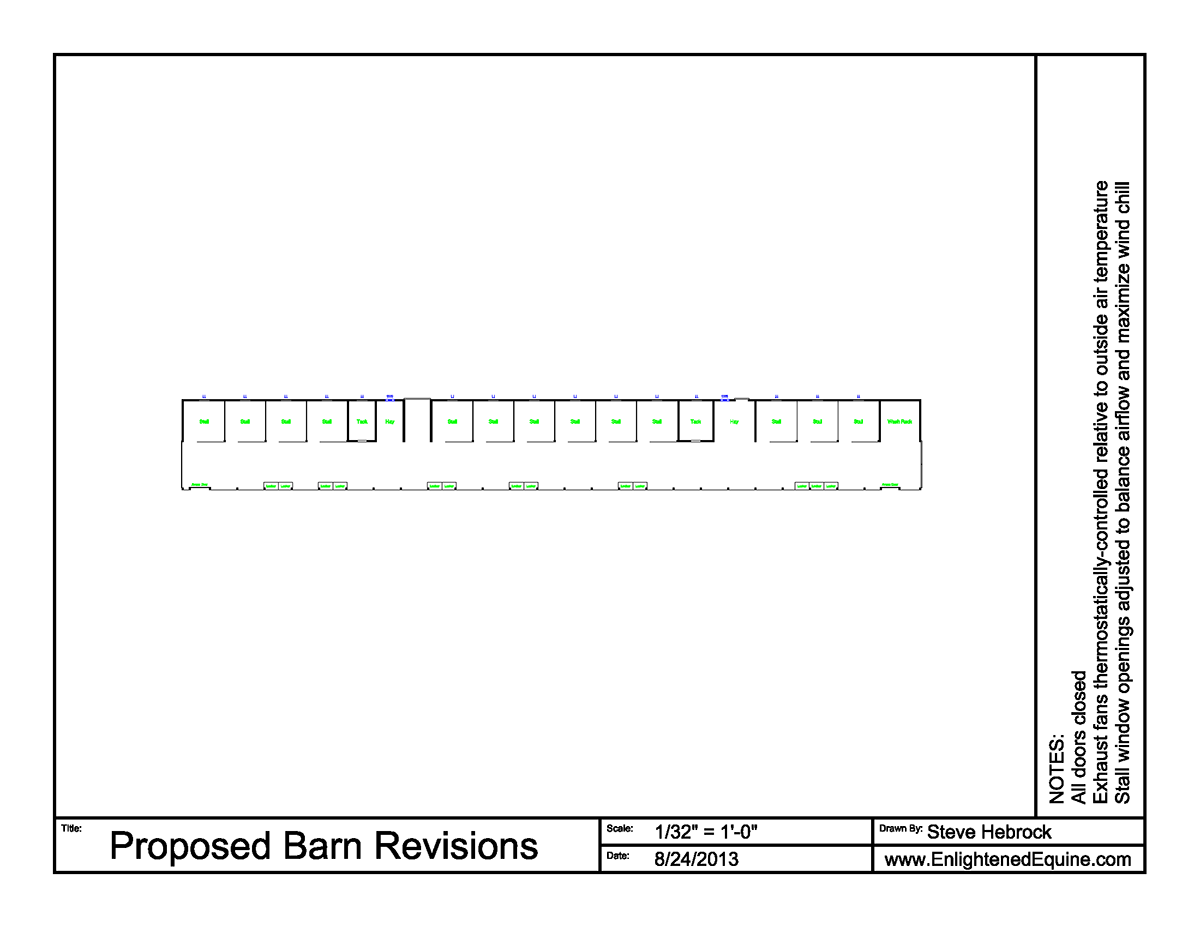

That means we need to think about making the barn more of a closed box, with a fan or fans mounted through the wall of the box to pull the warmer inside air out of the barn and, thereby, draw in cooler outside air through openings in our box. We can take advantage of the faster air movement that occurs at the openings by using the stall windows as our air inlets, and adjusting how open or closed they are to both balance the airflow and create a fan-like effect (same thing – a pressure difference) to blow air on our horses and utilize wind chill for additional perceived cooling. It’s also important to turn the fans on only when the inside temperature is higher than the outside; otherwise, you’ll be heating the barn! So you need a thermostat arrangement that will compare inside and outside temperatures in carefully-chosen locations (maybe more than one location inside the barn), and turn on the fans accordingly. Here’s my proposed fan placement for the barn I’ve been describing –

Choosing fan quantity, size, and location is relatively simple. First, look for possible mounting places in the barn that are as equidistant from as many stalls as possible, so with the stall windows open the same amount, the quantity of air moving into and out of each stall is about the same. If what I’m describing isn’t quite clear, it may help to imagine a round barn with stalls placed around the perimeter, with a window in each stall. Placing the fan in the center of the roof would give fairly even airflow throughout the stalls, assuming the windows were all open the same amount. If you were to place the fan directly over one of the stalls, though, most of the air movement would be from that stall unless you started closing windows closer to the fan to pull air from the more distant stalls. You’d like to avoid that scenario as much as possible, because you want all of the horses to experience the same benefit from wind chill. Since warm air rises, try to find locations closer to the ceiling; don’t rule out using roof-mounted fans, either. Many barns, like the one in the example, are long and narrow, so you may end up with two or three sites. You shouldn’t, however, need any more than that in any horse barn I’ve seen, as you’ll soon see from the math.

Next, you’ll have to calculate fan size. For that, you’ll need three pieces of information: the number of fans, the volume of the barn in cubic feet, and the air turnover rate, which is the amount of time in minutes it takes to completely replace the air in the barn. Typical values for air turnover rate range from 10 to 20 minutes. Rather than lead you through the formulas, though, I decided to create a very simple MS Excel spreadsheet to make it easier, since I suspect many of you (like my students) both despise math and/or have forgotten most of what you learned in high school! If you have anything other than a flat, sloped, or peaked roof (like a gambrel roof, for example), you’ll have to do more measuring to calculate an accurate volume. But “guesstimating” the numbers in this application is generally sufficient. Here’s the spreadsheet –

Barn Ventilation Fan Calculator

Once you have the CFM per fan calculated, it’s just a matter of choosing a fan or fans with sufficiently-high airflow to meet or exceed the required value. To completely replace the air in the barn in 10 minutes, my example barn needs two fans, each with a CFM rating of at least 2,500. Looking online at a fan supplier such as this one, I see a number of 16″ shutter-type exhaust fans with ratings over 2,500 CFM. On the other hand, if I’m content to replace the air every 15 minutes, the required CFM drops to 1,667 per fan, and I can use 12″ models instead. I do recommend both shuttered and heavy-duty fans, by the way, to minimize potential problems.

Now, the really interesting thing about all of this is the most common box fans used in barns are 20″ fans with CFM ratings of between 1,700 and 2,200 per fan. That means in my example barn, there’s already a total capacity of over 25,000 CFM – five times what’s necessary, with the ability to replace all of the air in the barn every 2 minutes – but it’s not working because the fans are not being properly used! So instead of fifteen 20″ fans running in my example barn, I can replace all of them with only two 16″ fans, and do a far better job of cooling the horses! Quite a revelation, right?

There’s much more to say, but this should at least get you thinking about more efficient, less expensive, and safer ways to cool your barn. I’ve already put a PDF version of this article in the Printable Article Archive that can be easily printed and shared with your barn-owning friends. More coming…