NOTE: This particular subject is of great interest to me because its exploration leads the logical person to question the very foundations of modern farriery. Foolishly, I began the writing process thinking I could say what needed to be said in a single post. But after I started putting my thoughts down, it quickly became evident there was no way I could accomplish what I’d set out to do with only one post. And so I’ll be presenting it as a series of articles instead, beginning with some anatomical and biomechanical background theory and concluding with the consequences of artificially manipulating hoof angles.

—

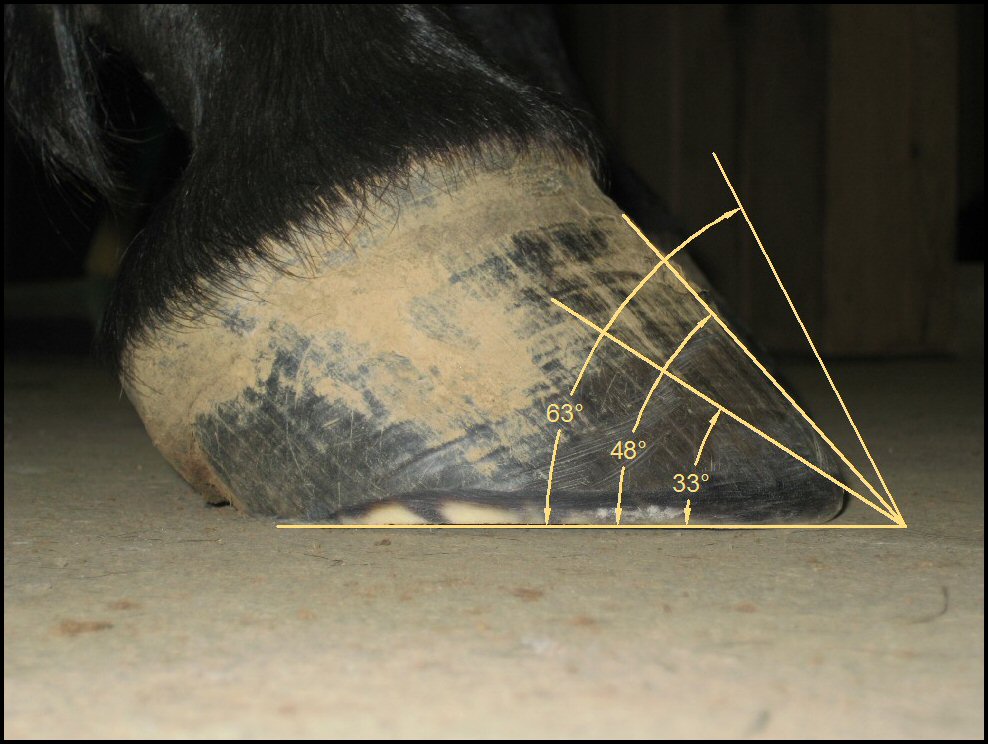

One of the most commonly misunderstood topics with respect to equine hooves is the subject of hoof angles. When hoof care professionals speak of “hoof angles,” they’re referring to the angle the dorsal hoof wall (at the toe) forms with respect to the ground, as shown in the following photo/diagram –

As I mentioned in Off His Rocker(s), many horse people place a great deal of emphasis on hoof angles. Owners think a particular angle is important for proper movement, or that the angles of hoof pairs must always match. Veterinarians and farriers are forever trying to enhance movement or increase comfort by deliberately manipulating hoof angles, which is accomplished by adjusting the relative amounts of bearing surface hoof wall at the toe and heel buttresses (“heels”) and/or by utilizing wedge shoes and/or wedge pads. Adding (or not removing) length at the toe relative to the heels will lower the angle, while (more commonly) adding or not removing length at the heels will increase the hoof angle. And yet, these angles are not arbitrary. As you’ll learn, there is only one correct angle for every horse’s hoof, and artificially varying that angle is not without consequences. But more on that later; we’ll spend the rest of this post covering some necessary background information and relevant terminology.

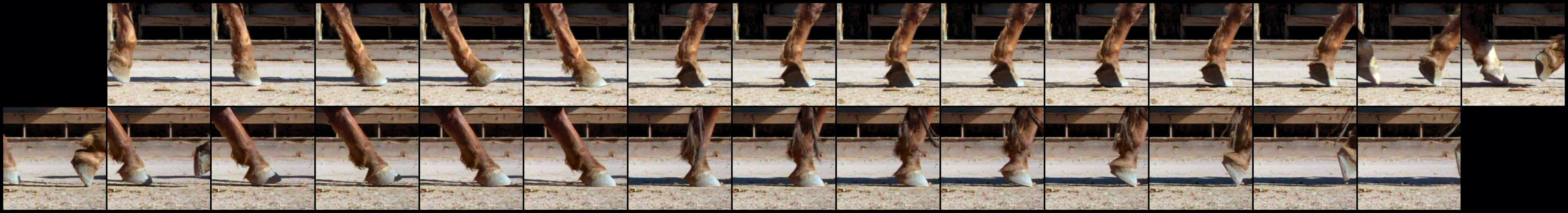

If you click below on what appears to be a tiny strip, you’ll see it’s actually a series of 33 sequential frames extracted from my upcoming video on hoof landings. In the leftmost frame, the horse’s front left hoof has just made contact with the ground, and in the rightmost frame, the front left hoof has finished one complete stride and once again made ground contact –

The distance traveled along the ground from one end of the photos to the other is defined as the horse’s stride length. For any particular hoof, one stride consists of two parts: the support phase (also called the stance phase), where the limb is bearing weight (shown in the first 2o images), and the swing phase, where the hoof has left contact with the ground and is in flight (shown in frames 21 through 33). If we were to then tape a light to the horse’s front hoof and view the path the light traces as the hoof leaves the ground and then lands, the result would look like the following composite photo/diagram –

This path is known as the flight arc. Note there are several interesting things we can learn from this photo. First, the flight arc is fairly shallow, with no large excursion off the ground. This, of course, varies with the breed and conformation of the horse, but like many other horses, this horse has much more forward motion than vertical height apparent in the flight arc. Second, you’ll see that the gentle peak in the flight arc occurs soon after the hoof leaves the ground. And third, notice that the rear hoof’s contact point with the ground is slightly past where the front foot began its flight.

The next sequence of photos from the same upcoming video shows a (different) properly-trimmed horse at the walk. The top set is the landing and takeoff of a front foot, while the bottom set is a rear foot. To save space, I’ve put a break in the sequence between when the foot finally lands and when it again begins its rotation off the ground, evidenced by the radically different angles of the cannon bones –

Notice how smoothly the hoof lands – perfectly flat – and then leaves the ground. The breakover (time) is the time difference between when the heels leave the ground (frame 7 in the top sequence) and when the toe leaves the ground (frame 9 in the top sequence).

Keep in mind that it’s not possible to calculate exact times and positions from these video excerpts because each frame is 1/30 of a second apart, and motion has occurred in between the captured images. Another interesting phenomenon apparent in these video stills is the blurring due to motion, most prominent when the hoof is farthest from the ground. That’s because the hoof decelerates to near zero as it prepares to make contact, and accelerates again as it moves higher in the flight arc.

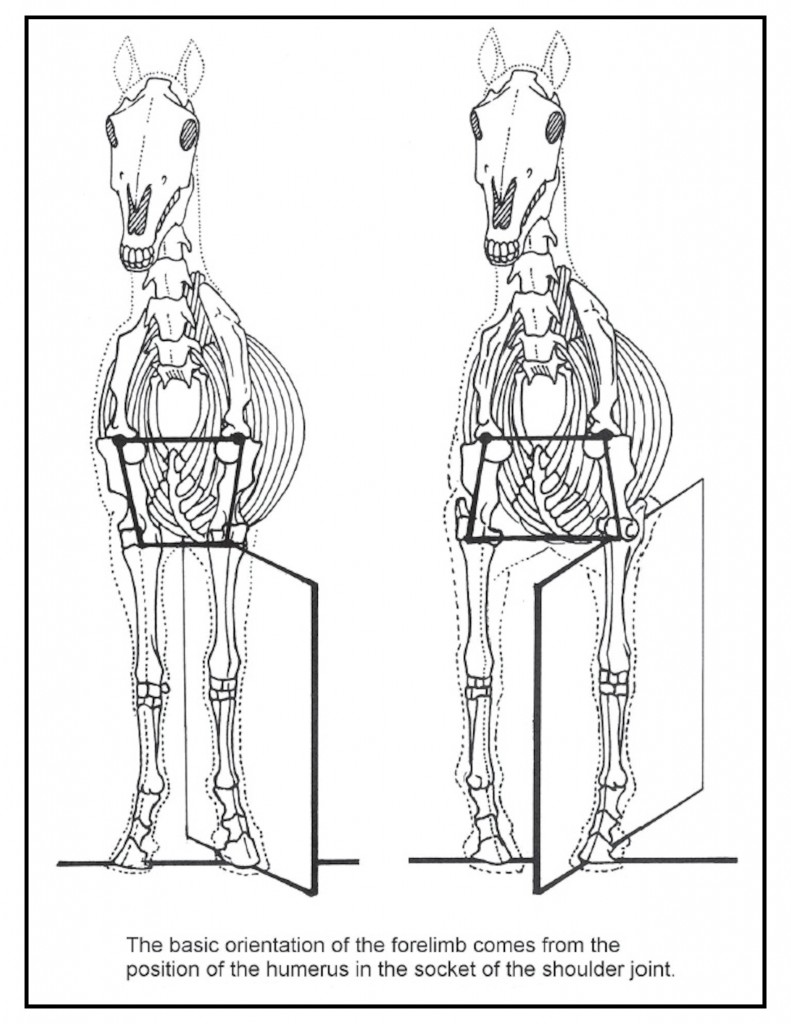

Let’s now look at what determines the “parallelness” of the pairs of limbs i.e. whether or not the horse’s toes point directly forward, or whether they turn out or turn in. Interestingly, the plane defined by a limb’s motion is determined not by the joints of the lower limb, but by the construction of the horse’s shoulder or hip. I particularly like this illustration from Dr. Deb Bennett’s Principles of Equine Orthopedics –

The reason for identifying these particular movement parameters is because these are the characteristics veterinarians and farriers endeavor to change through trimming and shoeing: the stride length, the flight arc, the landing, breakover time, and the plane of limb movement. Most of these are thought to be connected directly or indirectly with hoof angles. Over the next few posts, we’ll examine whether or not these connections are real, and see what the data actually tells us about changing, or attempting to change, these gait characteristics.

The reason for identifying these particular movement parameters is because these are the characteristics veterinarians and farriers endeavor to change through trimming and shoeing: the stride length, the flight arc, the landing, breakover time, and the plane of limb movement. Most of these are thought to be connected directly or indirectly with hoof angles. Over the next few posts, we’ll examine whether or not these connections are real, and see what the data actually tells us about changing, or attempting to change, these gait characteristics.

In closing, let me share yet another video excerpt with you; this time of the landing and takeoff of a horse who happens to be shod –

Unlike the previous two examples, you’ll see this horse literally “slams” his feet down, even at the walk. And most importantly: this bad landing cannot be detected under normal viewing conditions. To the eye, this horse appears to land perfectly fine; it’s only when capture the movement on video and slow it down do we see just how bad this landing really is. Think about the implications of that next time someone tries to convince you that you should see a horse land heel-first!

Stay tuned…